In the previous post, we discussed inequalities in access to credit from the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), showing that, although fintech lenders had a small share of total PPP loan volumes, they provided important support for underserved borrowers. In this post, we ask whether smaller firms received the amount of PPP credit that they requested, and whether loans went to the hardest-hit areas and mitigated job losses. Our results indicate that fintech providers were a key channel in reaching minority-owned firms, the smallest of small businesses, and borrowers most affected by the coronavirus pandemic.

Did Smaller Firms Seek and Receive PPP Loans?

A request for a small dollar loan—defined as $25,000 or less in the Federal Reserve’s Small Business Credit Survey–may indicate credit demand by smaller firms that find such loans better suited to their business needs. In support of this interpretation, we find that firms with fewer employees, lower annual revenues, and women owners were more likely to apply for small loans, consistent with prior research that women-owned firms are smaller, on average, than those owned by men. For example, the median amount requested by nonemployer firms (those with no employees other than the owner) was just $12,000. Nonemployer firms were also more likely to apply to fintech lenders, perhaps because banks have higher fixed costs of processing small dollar loans than fintech firms. Since the PPP lender fees are a percentage of loan size (for example, 5 percent for loans of no more than $350,000), banks may have insufficient incentives to provide small PPP loans.

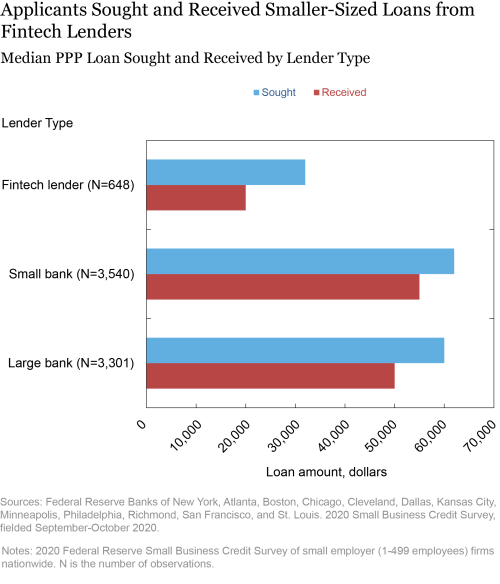

Among participants in the Small Business Credit Survey with between one and 499 employees, the median amount of PPP funds sought by those applying to fintech lenders was $32,000, compared to about $60,000 for bank applicants (see chart below). Fintech lenders approved loans with a median size of $20,000 (about 63 percent of the amount applied for) while banks approved loans with a median size of $50,000 (about 83 percent of the amount applied for). The lower shares of requested amounts that were approved for applicants to fintech lenders may reflect the smaller size of such firms, and their lesser familiarity with PPP rules. For example, the smallest businesses were less aware of PPP and less likely to apply to it, and, if they applied, they were more likely to apply late and face longer processing times.

Could small loan sizes indicate credit rationing by fintech lenders? This seems unlikely since applicants requested smaller loans. Historically, fintech firms have provided small dollar loans but at high interest rates, perhaps incentivizing applicants to request smaller loans. However, since rates are fixed in PPP, this incentive seems absent.

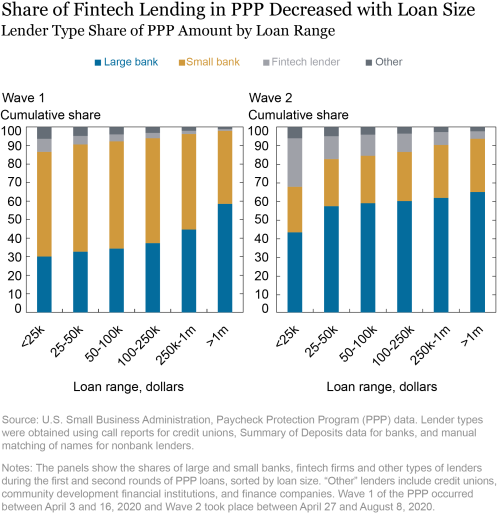

The survey results are corroborated with the PPP loan data. The chart below shows that fintech loans were concentrated in small loan sizes, especially those below $25,000. Fintech lenders’ share of loan volumes during Wave 1 of the PPP (April 3-16, 2020) was about 7 percent and 1 percent for loan sizes below $25,000 and above $1 million, respectively, and increased to 29 percent and 4 percent, respectively, during Wave 2 (April 27-August 8, 2020). The shares of small loans for large and small banks were 30 percent and 57 percent, respectively, during Wave 1 and 36 percent and 29 percent during Wave 2. In other words, the increase in fintech lending during Wave 2 mostly occurred in the smallest loan sizes. While all lenders increased their share of small loans from Wave 1 to Wave 2, the relative increase was greater for fintech lenders than banks. Prior research had also noted a substitution between fintech lenders and banks but not that this occurred for small sized loans.

Did Fintech Loans Reach Hard-Hit Borrowers?

Some design features of the PPP program and the importance of pre-existing banking relationships may have prevented PPP lenders from reaching borrowers most affected by the pandemic, at least during Wave 1, but smaller banks did better than large banks. Did fintech lenders improve on banks in targeting loans to borrowers most in need?

To answer this question, we regress a lender’s loans in a county as a share of its loans in the state on the share of a race or ethnic group residing in the county and measures of county characteristics (such as its education and income levels relative to the state). We find that fintech lenders provided more small loans (less than $25,000) in counties with higher fractions of Black residents during Wave 1. By comparison, small loans by banks during Wave 1 had a negative or no correlation with the fraction of Black residents in the county. These results highlight the outsized impact of the few fintech lenders that were authorized to provide PPP loans during Wave 1.

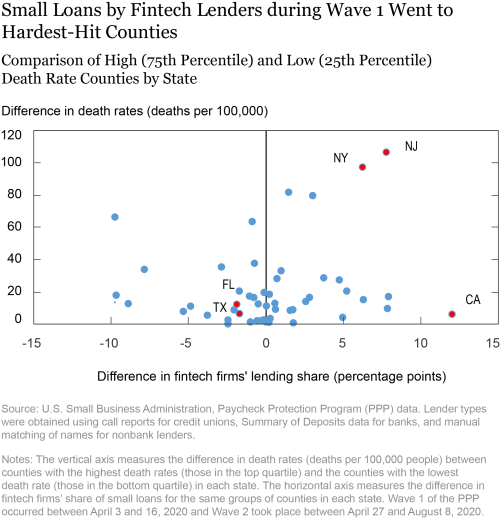

Did fintech loans go to counties with higher COVID-related deaths? In the regressions, we include an additional explanatory variable: the county’s death rate from COVID-19 on May 4, 2020 (for Wave 1) and May 27, 2020 (for Wave 2). The dates were selected to account for the fact that COVID-19 deaths lag the incidence of the disease. We find that fintech lenders provided more small loans (less than $25,000) in counties with higher death rates. This is illustrated in the scatter diagram below where the difference in death rates between the highest and lowest death rate counties in a state is plotted against the difference in fintech lenders’ share of small loans for those same counties. Fintech firms’ small loan shares have high correlation with death rates, especially in states with large geographical dispersion in death rates. For example, in New York, fintech lenders’ share of small loans was almost twice as large in the counties with the highest death rates as compared to counties with the lowest death rates. By comparison, bank loan shares were statistically uncorrelated with death rates during Wave 1. During Wave 2, loans of all lenders had a similar correlation with death rates, consistent with other research.

Were PPP Loans Associated with More Rehires?

Firms that applied for emergency assistance (PPP or other government programs like the EIDL) were more adversely affected by the pandemic than those that did not. Half of firms that completed an application had reduced their workforce, as compared to about 27 percent for firms that did not apply for emergency assistance. This was particularly true for Black-owned firms. About two-thirds of Black-owned firms that applied for emergency assistance had reduced their workforce while less than half of white-owned firms had done so.

When applicant firms received PPP loans, they were then more likely to rehire employees. More than three-fourths of firms that received PPP funds took actions to rehire employees compared to just over half of firms that did not apply for or receive PPP funds. Black-owned firms that received PPP were as likely as white-owned firms to have attempted to rehire their employees. However, among firms that did not receive PPP funds (either because they did not apply or they applied but were not approved), Black-owned firms were less likely than white-owned firms to attempt to rehire.

Our results do not establish that PPP loans caused more rehires since we do not account for credit demand effects. Nor can our data speak to the magnitude of job loss preventions, but prior research has found that the PPP had modest employment effects. However, it may have helped in other ways—for example, to enable firms to meet non-PPP loans and other non-payroll obligations and to improve their chances of survival.

Final Words

While fintech lenders accounted for a small share of total PPP loan volumes, they played an important role in serving minority owners and businesses that needed small loans but were less likely to receive them from other sources. These smallest of small establishments are critical in supporting vibrant commercial districts and have higher shares of female and minority entrepreneurs. Reflecting this, special efforts were made in the most recent round of PPP funding to make the program more attractive to sole proprietors, independent contractors, and the self-employed.

Jessica Battisto is a senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Outreach and Education Group.

Jessica Battisto is a senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Outreach and Education Group.

Nathan Godin is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Nathan Godin is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Claire Kramer Mills is an assistant vice president and director of community development analysis in the Bank’s Outreach and Education Group.

Claire Kramer Mills is an assistant vice president and director of community development analysis in the Bank’s Outreach and Education Group.

Asani Sarkar is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Asani Sarkar is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Jessica Battisto, Nathan Godin, Claire Kramer Mills, and Asani Sarkar, “Who Benefited from PPP Loans by Fintech Lenders?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, May 27, 2021, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2021/05/who-benefited-from-ppp-loans-by-fintech-lenders.html.

Additional Posts in This Series

COVID-19 and Small Businesses: Uneven Patterns by Race and Income

Who Received PPP Loans by Fintech Lenders?

Press Briefing

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics