More than four years have passed since the onset of the pandemic, which resulted in one of the sharpest and deepest economic downturns in U.S. history. While the nation as a whole has recovered the jobs that were lost during the pandemic recession, many places have not. Indeed, job shortfalls remain in more than a quarter of the country’s metro areas, including many in the New York-Northern New Jersey region. In fact, while employment is well above pre-pandemic levels in Northern New Jersey, jobs have only recently recovered in and around New York City, and most of upstate New York—like much of the Rust Belt—still has not fully recovered and has some of the largest job shortfalls in the country.

In this post, we examine the uneven geographic recovery from the pandemic recession, including why some places are finding it so difficult to recover. Many of the places that have not regained the jobs lost were hit particularly hard by the pandemic, leaving a deeper hole to dig out of. Further, these places tended to be slow-growing local economies leading up to the pandemic, leaving less momentum for a full recovery, and they face ongoing struggles finding the workers they need to grow. Indeed, with such persistent headwinds, many of these places are likely to continue to struggle to fully recover from the pandemic recession.

Most Places Have More Than Fully Recovered, But Many Have Not

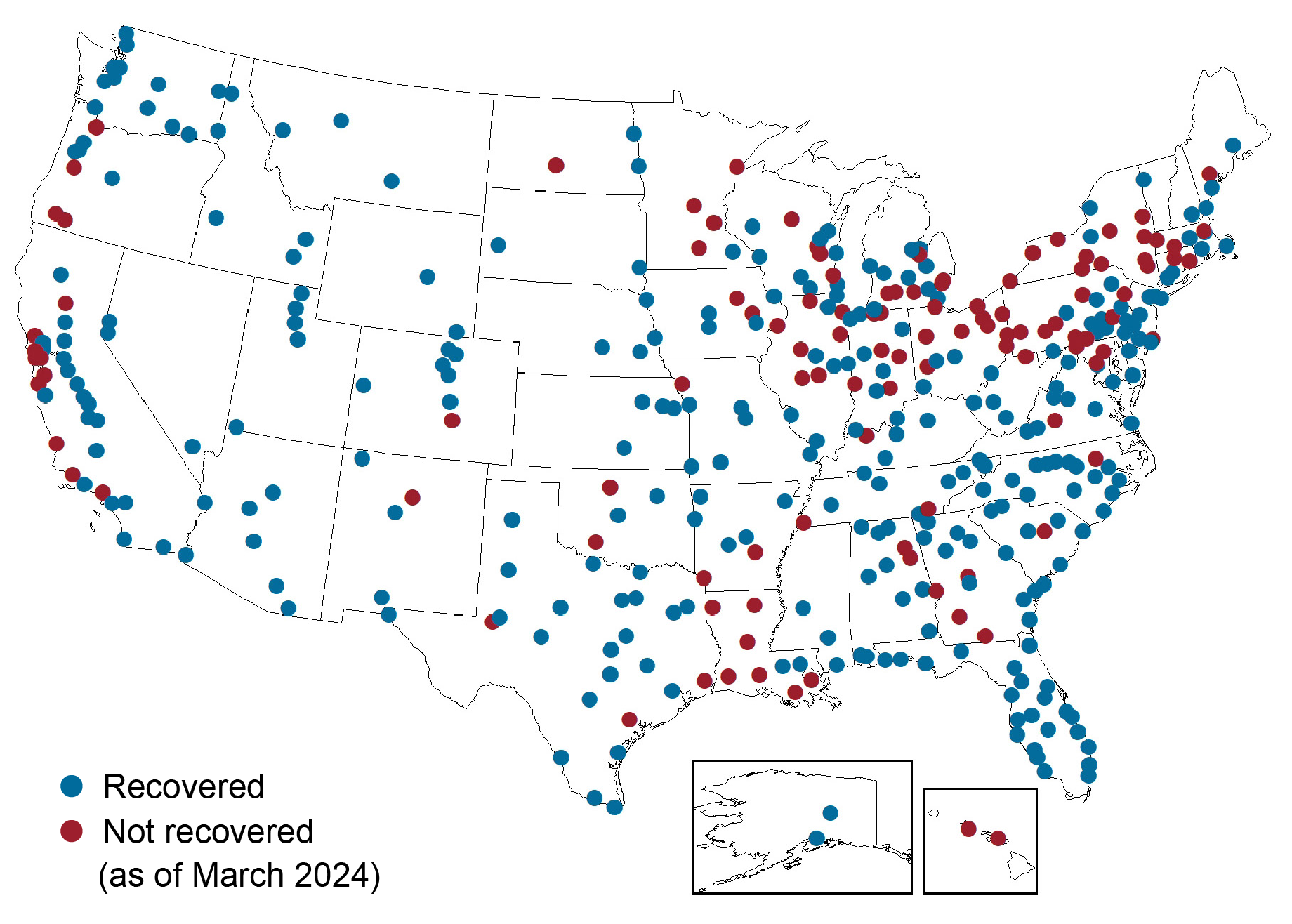

Employment fell nearly 15 percent in the United States between February 2020 and April 2020—a shockingly large decline in such a short period of time. The country had dug itself out of this massive hole by the summer of 2022, recovering all of the jobs that were lost, and employment is now nearly 4 percent above pre-pandemic levels. As the map below shows, however, the recovery has been uneven and remains incomplete in many places. Indeed, while most metro areas have recouped the jobs that were lost during the recession (shown as blue dots), more than 25 percent still have not (shown as red dots). Most of these areas are concentrated in the Rust Belt along the Great Lakes, though clusters are present in parts of the South—Louisiana in particular—as well as in California, Oregon, and Hawaii. In fact, employment is still more than 5 percent below pre-pandemic levels in New Orleans, and more than 3 percent below in Honolulu and San Francisco. Likewise, sizable job shortfalls remain in Cleveland, Detroit, and Pittsburgh. At the other end of the spectrum, employment in fast-growing parts of the country such as Austin, Boise, Phoenix, Raleigh, Charleston, and Sarasota is now more than 10 percent above pre-pandemic levels. (Download the full set of metro-area data and rankings).

An Uneven Geographic Recovery from the Pandemic Recession

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; Moody’s Economy.com.

Much of The New York-Northern New Jersey Region Is Still Way Behind

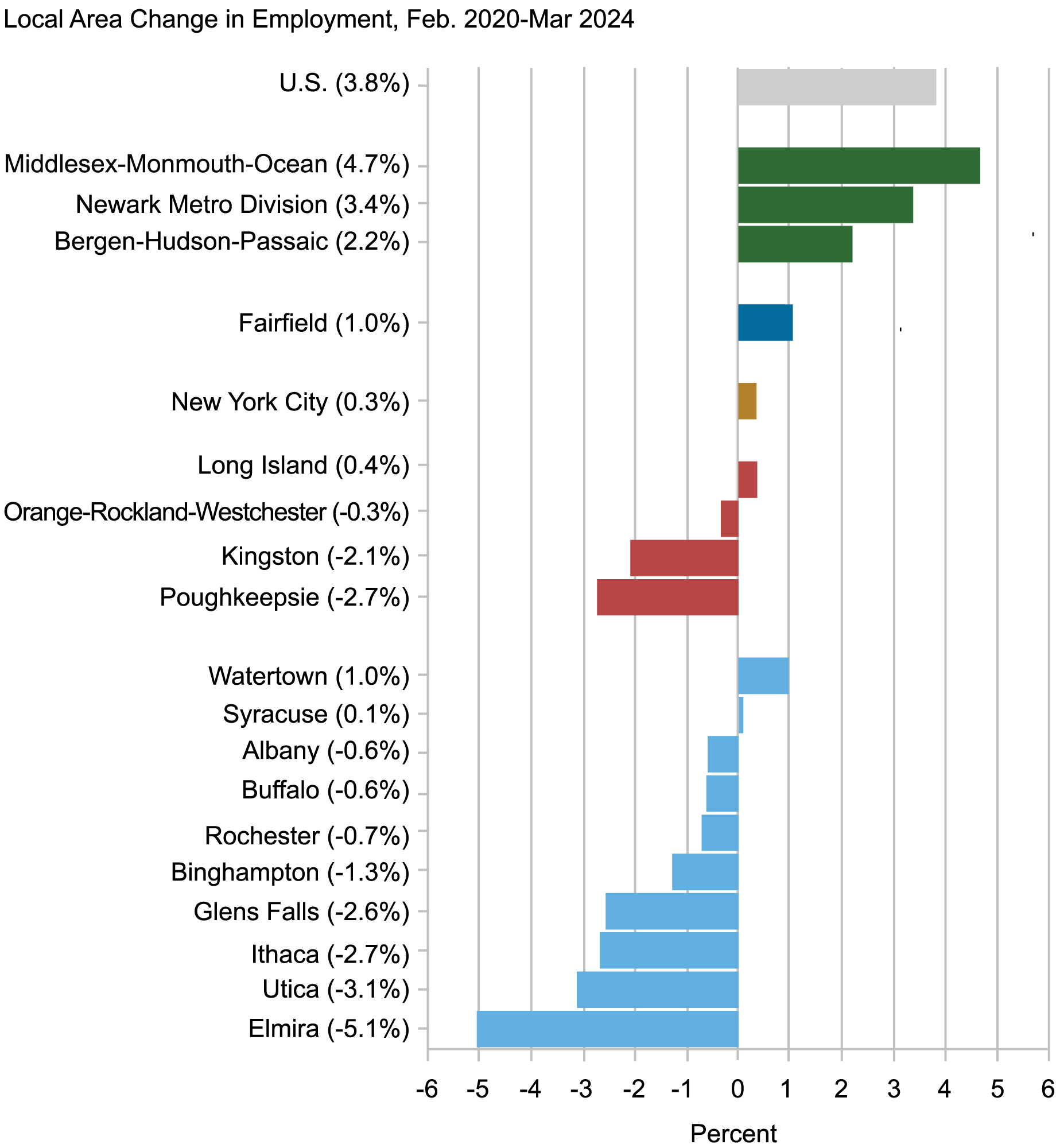

The New York-Northern New Jersey region was hit especially hard by the pandemic, and has been slow to recover. The chart below shows the change in employment from February 2020 to March 2024 for local areas in the region compared to the nation as a whole.

Large Job Shortfalls Remain in Much of the N.Y.-Northern N.J. Region

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; Moody’s Economy.com.

Employment is well above pre-pandemic levels in Northern New Jersey, though generally to a lesser extent than nationally, and is firmly above pre-pandemic levels in Fairfield, Conn. Though it took one-and-a-half years longer than for the nation as a whole, New York City has now recovered the jobs that were lost during the pandemic recession, but only just so, leaving it well behind the nation. Notably, the jobs gained in New York City during the recovery have not been the same as the jobs that were lost. Indeed, much of the City’s job growth has been in the healthcare sector, which is up almost 14 percent compared to pre-pandemic levels. And while there has been growth in high-paying sectors such as finance and business services during the recovery, lower-paying sectors such as retail, leisure & hospitality, and personal services that depend on foot traffic from office workers and visitors continue to lag.

While Long Island has just recently fully recovered to pre-pandemic employment levels, job shortfalls remain in much of the rest of New York State, including Kingston and Poughkeepsie as well as nearly every metro area in upstate New York, where some of the largest job shortfalls in the country remain. Indeed, Elmira’s employment level is still 5 percent below its pre-pandemic benchmark, ranking as the eighth-largest job deficit of all metro areas in the country. Utica, Glens Falls, Ithaca, and Poughkeepsie all have job deficits ranging between 2.6 and 3.1 percent, ranking among the twenty-five largest shortfalls in the nation. Focusing on upstate New York’s largest metros, Syracuse has now only just recovered the jobs that were lost, and Albany, Buffalo, and Rochester all have job deficits around 0.6 to 0.7 percent.

Why Are Some Places Finding It So Hard to Recover?

The metro areas that are lagging in the jobs recovery share some common features. First, many of them were hit particularly hard during the initial shock, leaving a bigger hole to dig out of. On average, the places that have not yet recovered experienced an employment decline of 16.1 percent during the pandemic recession compared to a 13.4 percent decline in the places that have recovered. While industry composition certainly played a role in the depth of the decline—in particular, local economies reliant on tourism suffered large losses—declines were quite steep in places where the pandemic first took hold. Specifically, clusters of job deficits persist in New York, California, and Michigan, all of which emerged as coronavirus hot spots and had outsized job declines early in the pandemic. Indeed, initial job losses in the New York-Northern New Jersey region averaged almost 19 percent, and parts of California and Michigan saw initial job losses well above 20 percent.

In addition, many of the places that have not recovered were slow-growth economies heading into the pandemic, leaving less momentum to grow and recover coming out of it. Indeed, the metro areas with job deficits saw average annual job growth of just 0.5 percent in the five years leading up to the pandemic, compared to 1.5 percent, on average, for those that have recovered. Over the past year, slower job growth in the areas that have not yet recovered has resumed.

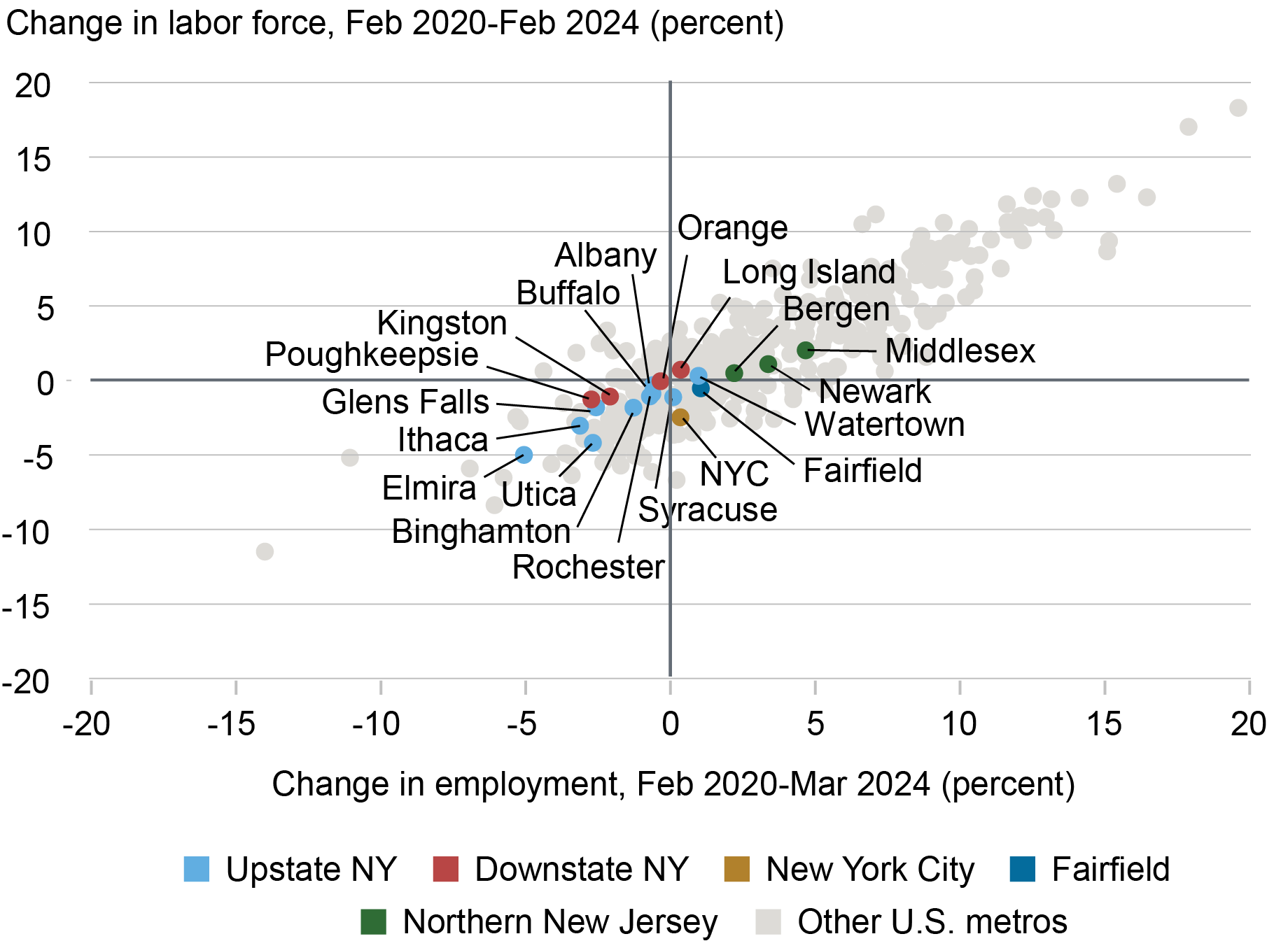

Further, many places that have not recovered just don’t have the workers to allow their local economies to grow. With persistent worker shortages across the country since the pandemic, labor has often been hard to find, and that’s been especially true in places that still have job deficits, as shown in the chart below. Here we plot pre-pandemic job gains/deficits for local areas against the change in that area’s labor force since the pandemic hit. While remote work has decoupled where people live and work to some extent, the vast majority of workers still live in commuting distance to their employers. Indeed, the clear upward-sloping pattern shows the close connection between job growth and the availability of workers both across the country and within the region.

Worker Availability Contributing to Persistent Job Shortfalls

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; Moody’s Economy.com.

Local areas shown in the upper right quadrant, including those in Northern New Jersey, have seen growth in their local labor forces, and employers are more able to find the workers they need. As a result, such places are seeing employment climb well above pre-pandemic levels. At the other end of the spectrum, areas in the lower left quadrant have seen their labor forces shrink and have job deficits. Parts of upstate New York such as Binghamton, Elmira, and Utica saw labor force declines, which were in fact already occurring before the pandemic hit, in part due to population aging and people leaving the area. Clearly, more people willing and able to work will be required to achieve a full recovery in this part of the region, but with ongoing long-term labor force decline, these places and others like them are likely to continue to struggle to gain back the jobs that were lost during the pandemic recession. New York City has been able to gain back the jobs that were lost despite a declining local labor force, largely because it can draw workers from a broader surrounding geographic area.

The New Normal Is the Old Normal

Four years after the pandemic hit, historical growth patterns have generally resumed throughout the country after a period of rapid recovery. The places that were growing more strongly before the pandemic have generally recovered and are growing more strongly today, while many places that lagged are still struggling to recover. Indeed, more than a quarter of the country has not gained back the jobs that were lost during the pandemic recession, including most of upstate New York. Some places in upstate New York were hit by a “triple whammy” of slow growth leading up to the pandemic that has now resumed, a deeper hole when the pandemic hit, and a declining labor force. As such, upstate New York, and many places like it, may well continue to struggle to reach employment levels seen before the pandemic.

Jaison R. Abel is the head of Urban and Regional Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Richard Deitz is an economic research advisor in Urban and Regional Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Jonathan Hastings is a research associate in Urban and Regional Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Joelle Scally is a regional economic advisor in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Jaison R. Abel, Richard Deitz, Jonathan Hastings, and Joelle Scally, “Many Places Still Have Not Recovered from the Pandemic Recession,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, May 7, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/05/many-places-still-have-not-recovered-from-the-pandemic-recession/

BibTeX: View |

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

We saw this in NOLA and Miss Gulf South after Katrina hit – disasters speed up by many years trends that are in progress. Insitutions and companies hanging on by a thread die, but new things can blossom from the disruption. In NOLA growth was inflow of laboroers for rebuilding and high school / college students working on relief efforts (some who returned after college to work).