James Narron and David Skeie

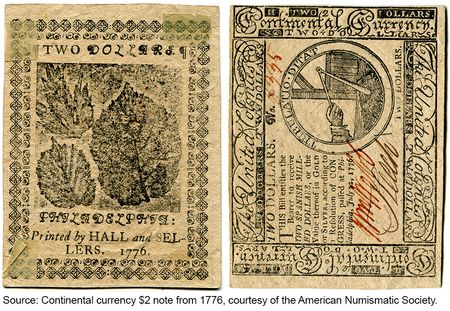

During the late 1770s, a newly founded United States began to run up significant debts to finance the American Revolution. With limited access to credit and little to no tax base, the Continental Congress issued the Continental to finance the war. But by the end of the decade, inflation was nearly 50 percent, a suit cost a million Continentals, and the phrase “not worth a Continental” had entered the national lexicon. With the help of our fourth U.S. president, James Madison, we review why the Continental experiment ended so badly.

Financing the Revolution

Readers of this series are by now familiar with the ever-changing link between the financing of wars and the rise of financial crises. First in the series, we covered the Kipper und Wipperzeit coin clipping crisis that was in part a result of struggles to pay for the Thirty Years’ War. A subsequent post noted that the monetary contraction caused by the Not So Great Re-Coinage of 1696 inhibited Britain’s ability to pay the armies engaged in the Nine Years’ War. Later, we examined how the Seven Years’ War led to a commodity boom, then the sudden crash of 1763.

At the onset of the American Revolution, the Continental Congress recognized that to effectively control the revolution, they would have to finance it. But the means of finance available to established nations, like access to credit and taxation, weren’t so readily available. The Continental Congress was reluctant to rely on taxation to fund the revolution, given the role of taxes in bringing on the war in the first place. Despite loans from France, the credit risk of additional loans to support a colonial rebellion without a reliable tax base seemed too high to most investors. Gold and silver coins had for years been flowing to Britain for purchases and they remained in such short supply that colonial trade was largely based on agricultural credit, as we noted in our last piece on the commodity crisis of 1772. But prior to the revolution, some colonial states with a strong tax base like New York and Pennsylvania had success with paper currency. So Congress turned to the printing press as the next best option to finance the revolution, and began issuing Continentals by mid-1775.

Not Worth a Continental

Initially, Continentals were used effectively to equip the army. However, Congress hadn’t prepared for a protracted war and had originally planned on redeeming Continentals beginning in 1779. By mid-1776, despite efforts by Congress to ensure investors that it would redeem the currency in full in gold or silver, Continental currency holders lost confidence in the colonial army’s ability to end the war quickly or for Congress to eventually back the currency through tax receipts, and Continentals began to lose their value.

Although Congress worked to create a sort of monetary union by seeking control over currency issue, and thus monetary policy, they were unable to do so, as states continued to issue their own currencies. By 1779, the Continental had depreciated to pennies on the dollar and inflation reached nearly 50 percent, giving rise to the expression “not worth a Continental.” Congress considered a number of remedies including devaluation, raising taxes, and tying currency issuance to future tax receipts—like a revenue bond—but ultimately elected to cease issuing currency altogether. By mid-1781, Continentals stopped circulating. The Continental army thus had to seize necessary provisions in order to continue to wage war, providing IOUs in return.

As future president James Madison pointed out in a 1779 essay, the value of money was dependent on the credit of the state issuing it rather than on its quantity. The protracted war had created a massive public debt and little confidence that the nation could pay it off. But as we noted in the South Sea Bubble post, there was soon competition to take on the national debt, this time between the states and Congress, for the right to control the debt meant the right to control the means of paying off the debt—in this case, taxation.

Short and Long Bobs

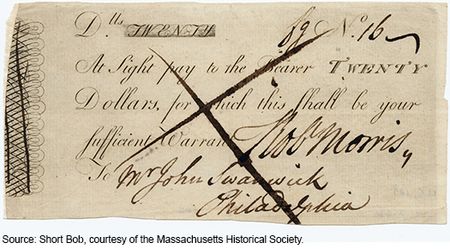

Although the war ended in 1783, the finances of the United States remained somewhat chaotic through the 1780s. In 1781, successful merchant Robert Morris was appointed superintendent of finance and personally issued “Morris notes”—commonly called Short and Long Bobs based on their tenure or time to maturity—and thus began the long process to reestablish the government’s credit. In 1785, the dollar became the official monetary unit of the United States, the first American mint was established in Philadelphia in 1786, and the Continental Congress was finally given the power of taxation to pay off the debt in 1787, thus bringing together a more united fiscal, currency, and monetary policy.

While we’ve noted in previous posts that lessons often last only a lifetime, so deep was the public distrust of government money that it wasn’t until the Civil War that paper money was again issued in any substantial quantity.

Eurobonds and the European Debt Crisis

In a previous post on the Mississippi Bubble, we asked readers if Europe needed a united fiscal policy, along with united currency and monetary policies. We also asked their views on whether a united fiscal policy in the Eurozone should include Eurozone debt as well as centralized fiscal transfers, or perhaps even collection of taxes. And views were mixed. While a comment by TheTweetCzar thought that a united fiscal policy in Europe was indeed needed along with the united currency and monetary policies, one by Thinker thought that a united policy in Europe would be dependent on getting Germany to agree. These two views reflect much of the debate about Eurobonds as a possible solution to the European debt crisis. While Italy and Greece spoke out in favor of a Eurobond, with Italian Economic Minister Giulio Tremonti famously calling it the master solution to the debt crisis, Germany has been against at least the timing of issuing a Eurobond. Perhaps as Kalebrg astutely suggested, integration may need to take place organically over several generations.

The experience of the Continental Congress raises questions beyond those we asked in our Mississippi post. Could Eurobonds issued by the Eurozone, if ever issued, hold value without centralized Eurozone taxation? And what about the Euro currency has allowed it to attain reserve currency status without centralized taxation? The U.S. experience of issuing Continentals and debt without centralized taxation shows that, even with united governmental powers, there was much difficultly in achieving Congressional approval for taxation. In an even less politically united Eurozone, is the concept of unified taxation too far afield? Tell us what you think.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

James Narron is a senior vice president and cash product manager at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

David Skeie is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

unified taxation is a long term neccesity but i dont see any evidence that the germans want to pay for the failure of others secondly tax evasion is prolific in the mediteranean countries something the germans are acutely aware of. the whole thing is a farce a political step too far and should be dismantled ..but of course i am a brit you would expect me to say that