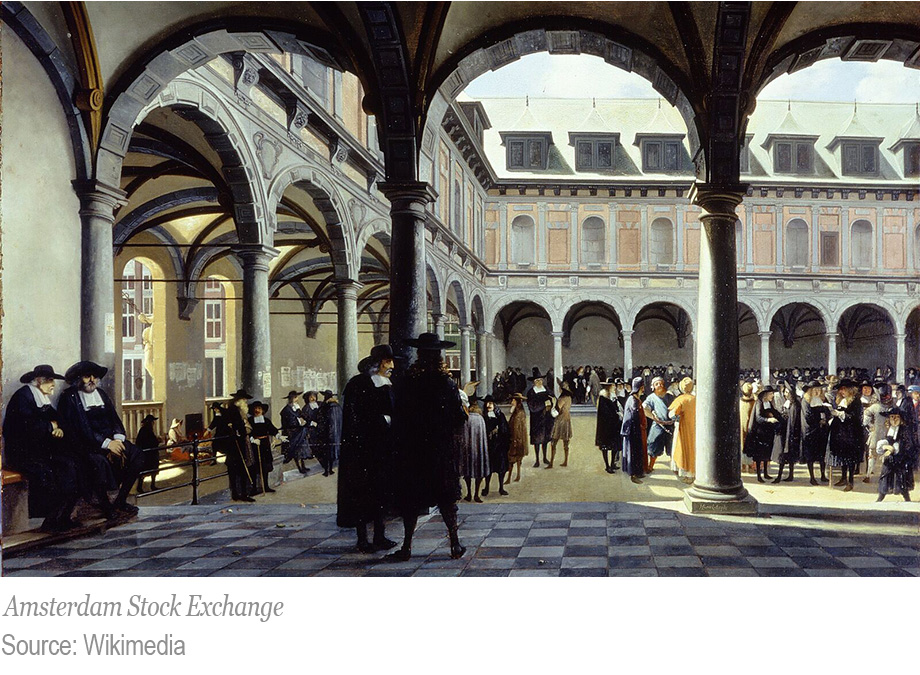

The First Global Credit Crisis

June 2022 marks the 250th anniversary of the outbreak of the 1772-3 credit crisis. Although not widely known today, this was arguably the first “modern” global financial crisis in terms of the role that private-sector credit and financial products played in it, in the paths of financial contagion that propagated the initial shock, and in the way authorities intervened to stabilize markets. In this post, we describe these developments and note the parallels with modern financial crises.

Refinance Boom Winds Down

Total household debt balances continued their upward climb in the first quarter of 2022 with an increase of $266 billion; this rise was primarily driven by a $250 billion increase in mortgage balances, according to the latest Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Creditfrom the New York Fed’s Center for Microeconomic Data. Mortgages, historically the largest form of household debt, now comprise 71 percent of outstanding household debt balances, up from 69 percent in the fourth quarter of 2019. Driving the increase in mortgage balances has been a high volume of new mortgage originations, which we define as mortgages that newly appear on credit reports and includes both purchase and refinance mortgages. There has been $8.4 trillion in new mortgage debt originated in the last two years, as a steady upward climb in purchase mortgages was accompanied by an historically large boom in mortgage refinances. Here, we take a close look at these refinances, and how they compare to recent purchase mortgages, using our Consumer Credit Panel, which is based on anonymized credit reports from Equifax.

How the Fed’s Overnight Reverse Repo Facility Works

Daily take-up at the overnight reverse repo (ON RRP) facility increased from less than $1 billion in early March 2021 to just under $2 trillion on December 31, 2021. In the second post in this series, we take a closer look at this important tool in the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy implementation framework and discuss the factors behind the recent increase in volume.

Credit Card Trends Begin to Normalize after Pandemic Paydown

Today, the New York Fed’s Center for Microeconomic Data released its Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit for the third quarter of 2021. Overall debt balances increased, bolstered primarily by a sizeable increase in mortgage balances, and for the second consecutive quarter, an increase in credit card balances. The changes in credit card balances in the second and third quarters of 2021 are remarkable since they appear to be a return to the normal seasonal patterns in balances. In a Liberty Street Economics post earlier this year we wrote about some demographic variation in these balance changes and the likely role of stimulus checks and forbearance programs in helping borrowers pay down expensive revolving debt balances. Here, we’ll take a fresh look at credit card balances and at the dynamics behind new and closing credit card accounts and limit changes, to examine how credit access and usage continue to evolve. The Quarterly Report and this analysis are based on our Consumer Credit Panel, which is itself based on Equifax credit data.

Does the Rise in Housing Prices Suggest a Housing Bubble?

House prices have risen rapidly during the pandemic, increasing even faster than the pace set before the 2007 financial crisis and subsequent recession. Is there a risk that another dangerous housing bubble is developing? This is a complicated question, and the answer has many components. This post, the first of two, provides a more detailed look at the recent rise in home prices by breaking it down geographically, with a comparison to the pre-2007 bubble. The second post looks at the potential risks to financial stability by comparing the currently outstanding stock of mortgage debt to the period before the financial crisis and projecting defaults should prices decline.

Forbearance Participation Declines as Programs’ End Nears

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Center for Microeconomic Data today released its Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit for the second quarter of 2021. It showed that overall household debt increased at a quick clip over the period, with a $322 billion increase in balances, boosted primarily by a 2.8 percent increase in mortgage balances, a 2.2 percent increase in credit card balances, and a 2.4 percent increase in auto balances. Mortgage balances in particular were boosted by a record $1.22 trillion in newly originated loans. Although some borrowers are originating new loans, struggling borrowers remain in forbearance programs, where they are pausing repayment on their debts and creating an additional upward pressure on outstanding mortgage balances.

Credit, Income, and Inequality

Access to credit plays a central role in shaping economic opportunities of households and businesses. Access to credit also plays a crucial role in helping an economy successfully exit from the pandemic doldrums. The ability to get a loan may allow individuals to purchase a home, invest in education and training, or start and then expand a business. Hence access to credit has important implications for upward mobility and potentially also for inequality. Adverse selection and moral hazard problems due to asymmetric information between lenders and borrowers affect credit availability. Because of these information issues, lenders may limit credit or post higher lending rates and often require borrowers to pledge collateral. Consequently, relatively poor individuals with limited capital endowment may experience credit denial, irrespective of the quality of their investment ideas. As a result, their exclusion from credit access can hinder economic mobility and entrench income inequality. In this post, we describe the results of our recent paper which contributes to the understanding of this mechanism.

Hold the Check: Overdrafts, Fee Caps, and Financial Inclusion

The 25 percent of low-income Americans without a checking account operate in a separate but unequal financial world. Instead of paying for things with cheap, convenient debit cards and checks, they get by with “fringe” payment providers like check cashers, money transfer, and other alternatives. Costly overdrafts rank high among reasons why households “bounce out” of the banking system and some observers have advocated capping overdraft fees to promote inclusion. Our recent paper finds unintended (if predictable) effects of overdraft fee caps. Studying a case where fee caps were selectively relaxed for some banks, we find higher fees at the unbound banks, but also increased overdraft credit supply, lower bounced check rates (potentially the costliest overdraft), and more low-income households with checking accounts. That said, we recognize that overdraft credit is expensive, sometimes more than even payday loans. In lieu of caps, we see increased overdraft credit competition and transparency as alternative paths to cheaper deposit accounts and increased inclusion.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics