The Rise in Deposit Flightiness and Its Implications for Financial Stability

Deposits are often perceived as a stable funding source for banks. However, the risk of deposits rapidly leaving banks—known as deposit flightiness—has come under increased scrutiny following the failures of Silicon Valley Bank and other regional banks in March 2023. In a new paper, we show that deposit flightiness is not constant over time. In particular, flightiness reached historic highs after expansions in bank reserves associated with rounds of quantitative easing (QE). We argue that this elevated deposit flightiness may amplify the banking sector’s response to subsequent monetary policy rate hikes, highlighting a link between the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet and conventional monetary policy.

The Fed’s Treasury Purchase Prices During the Pandemic

In March 2020, the Federal Reserve commenced purchases of U.S. Treasury securities to address the market disruptions caused by the pandemic. This post assesses the execution quality of those purchases by comparing the Fed’s purchase prices to contemporaneous market prices. Although past work has considered this question in the context of earlier asset purchases, the market dysfunction spurred by the pandemic means that execution quality at that time may have differed. Indeed, we find that the Fed’s execution quality was unusually good in 2020 in that the Fed bought Treasuries at prices appreciably lower than prevailing market offer prices.

Anatomy of the Bank Runs in March 2023

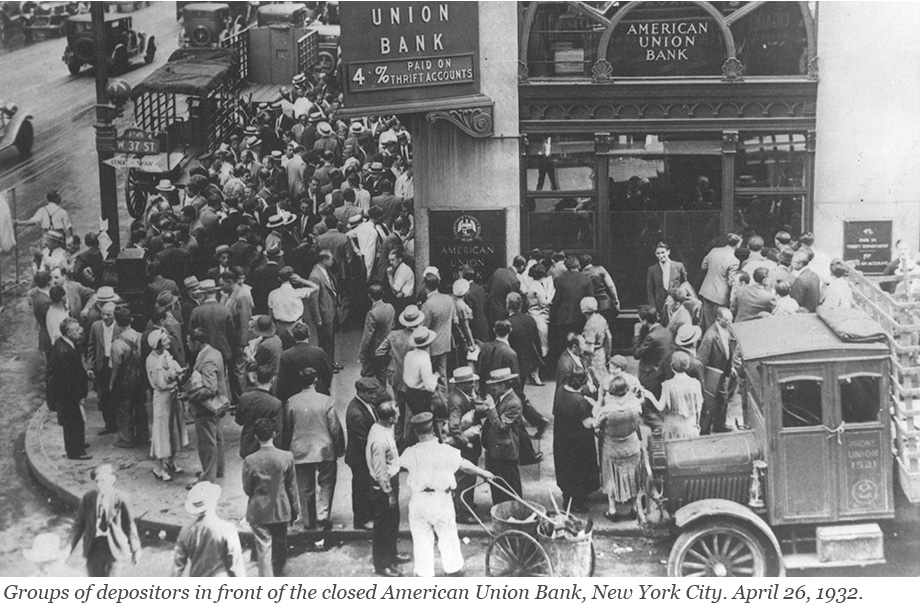

Runs have plagued the banking system for centuries and returned to prominence with the bank failures in early 2023. In a traditional run—such as depicted in classic photos from the Great Depression—depositors line up in front of a bank to withdraw their cash. This is not how modern bank runs occur: today, depositors move money from a risky to a safe bank through electronic payment systems. In a recently published staff report, we use data on wholesale and retail payments to understand the bank run of March 2023. Which banks were run on? How were they different from other banks? And how did they respond to the run?

Documenting Lender Specialization

Robust banks are a cornerstone of a healthy financial system. To ensure their stability, it is desirable for banks to hold a diverse portfolio of loans originating from various borrowers and sectors so that idiosyncratic shocks to any one borrower or fluctuations in a particular sector would be unlikely to cause the entire bank to go under. With this long-held wisdom in mind, how diversified are banks in reality?

Why Do Banks Fail? Bank Runs Versus Solvency

Evidence from a 160-year-long panel of U.S. banks suggests that the ultimate cause of bank failures and banking crises is almost always a deterioration of bank fundamentals that leads to insolvency. As described in our previous post, bank failures—including those that involve bank runs—are typically preceded by a slow deterioration of bank fundamentals and are hence remarkably predictable. In this final post of our three-part series, we relate the findings discussed previously to theories of bank failures, and we discuss the policy implications of our findings.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics