Several academic papers have documented investors’ willingness to pay a premium to hold money-like assets and focused on its implications for financial stability. In a New York Fed staff report, we estimate such premium using a quasi-natural experiment, the recent reform of the money market fund (MMF) industry by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

Money-Likeness and the SEC Reform

As discussed in a previous Liberty Street Economics blog post, the reform, which went into effect in October 2016, affected different segments of the MMF industry differently. In particular, prime MMFs were forced to adopt a system of gates and fees; moreover, prime MMFs catering to institutional investors were forced to float their net asset values. In contrast, government MMFs were unaffected by the new regulation.

Why can the effects of the MMF reform help us understand investors’ preference for money-like assets? A salient characteristic of money-like assets is their information insensitivity: for an asset to be used in transactions, agents must not worry about its future value. For this reason, money-like assets are usually short-term, liquid, debt‑like securities.

Before the SEC reform, MMF shares were the typical example of a money‑like asset: they were callable, redeemable at par, and had very little (at least, in investors’ perception) credit risk. This applied equally to government funds, which can only invest in Treasuries, agency debt, and repos collateralized by these securities, and to prime funds, which can also invest in high-quality, privately-issued unsecured debt. It also applied equally to funds with a retail clientele (retail funds) and those with an institutional clientele (institutional funds).

By forcing prime MMFs to adopt a system of gates and fees, the SEC made prime funds less money-like than government funds. And by forcing prime institutional MMFs to adopt a floating net asset value, the reform made institutional prime funds even less money-like.

A Quasi-Natural Experiment: The “Diff-in-Diff” Approach

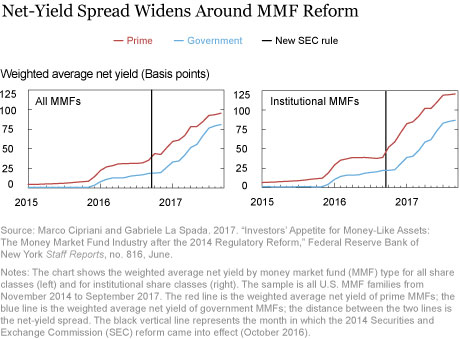

In our paper, we exploit the differential impact of the SEC reform on the different segments of the MMF industry as a quasi-natural experiment to estimate the premium investors are willing to pay for money-likeness. In particular, we look at the difference between the net yield offered by prime MMFs and that offered by government MMFs (the net-yield spread) and test whether such difference increased around the implementation of the reform (that is, we employ a difference-in-differences approach). Holding everything else constant, if investors value the money-likeness of their MMF shares, we expect the net-yield spread between prime and government MMFs to widen, and to do so to a greater extent for institutional funds.

This is indeed what happened! As the charts below show, in the months before the reform went into effect, the prime-government net-yield spread widened from 7 basis points in November 2015 to 24 basis points in October 2016; such widening of the spread is even more pronounced if we zoom in on the institutional segment of the MMF industry.

The widening spread can be interpreted as a measure of the convenience yield investors are willing to pay to keep the money-like feature of their MMF shares—that is, the value of the liquidity services that are enjoyed when investing in money-like assets.

Estimating the Premium for Money-Likeness

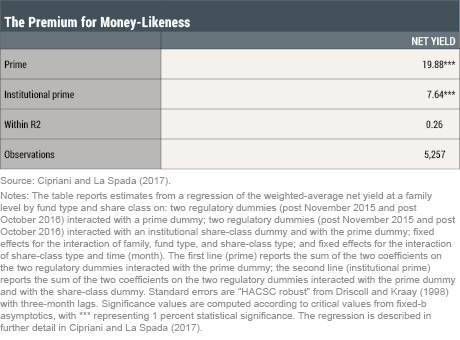

Of course, in the real world, “everything else” is never constant: many factors affect the yield spread between prime and government funds, and these factors may have changed around the implementation of the SEC rule. With a regression approach, we can control for this and, at the same time, obtain an estimate of the premium for money-likeness. The regression results are reported in the table below.

The coefficient in the first row of the table represents the increase in the spread between the average net yields of prime and government MMFs catering to retail investors around the implementation of the SEC regulation. On average, the spread was about 20 basis points higher as a result of the rule change. This estimate represents the value that investors attach to the fact that, after the rule, government funds were not forced to adopt a system of gates and fees and therefore retained the money-like feature of being liquid and short-term investments.

The second coefficient measures the additional increase in spread, approximately 8 basis points, that occurred in the institutional subsegment of the MMF industry. This estimate represents the value that investors attach to the fact that, after the rule, retail prime funds (and government funds) continued to offer a fixed-value product, a salient characteristic of money-like assets, whereas institutional prime MMFs were forced to float their net asset values.

Conclusion

The post-crisis SEC reform of the MMF industry affected the various segments of the MMF industry differently, providing researchers with a unique opportunity to estimate the premium that investors are willing to pay to hold money-like assets through a quasi-natural experiment. The increase in the spread between prime and government MMFs around the regulatory change shows that such premium is statistically significant and quantitatively important.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Marco Cipriani is an officer in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Gabriele La Spada is an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Marco Cipriani and Gabriele La Spada, “The Premium for Money-Like Assets,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), July 18, 2018, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2018/07/the-premium-for-money-like-assets.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

When the SEC changed the money market account rules, all brokers discontinued the use of prime money market accounts as settlement accounts for transactions. They forced investors to use government money market accounts instead of prime money market accounts. The result was a large movement out of prime and into government money market accounts. This tells us something about the government’s ability to force a change in behavior, but it does not reveal anything about investors’ preference or risk aversion.