Deposits make up an $18 trillion market that is simultaneously the main source of bank funding and a critical tool for households’ financial management. In a prior post, we explored how deposit pricing was changing slowly in response to higher interest rates as of 2022:Q2, as measured by a “deposit beta” capturing the pass-through of the federal funds rate to deposit rates. In this post, we extend our analysis through 2022:Q4 and observe a continued rise in deposit betas to levels not seen since prior to the global financial crisis. In addition, we explore variation across deposit categories to better understand banks’ funding strategies as well as depositors’ investment opportunities. We show that while regular deposit funding declines, banks substitute towards more rate-sensitive forms of finance such as time deposits and other forms of borrowing such as funding from Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLBs).

Deposit Betas

We estimate the evolution of deposit betas using data from bank holding company (BHC) regulatory filings (FR Y-9C). To infer the annualized rates being paid on deposits, we sum across all BHCs and scale the interest expense paid on deposits by the average of the corresponding deposit balance during the quarter. Although we focus on the rates paid on interest-bearing (IB) deposits, we also consider all deposits in several figures. We use the industry-level of deposits given our interest in the overall pass-through of monetary policy to deposit rates, but we will explore size differences in a future post.

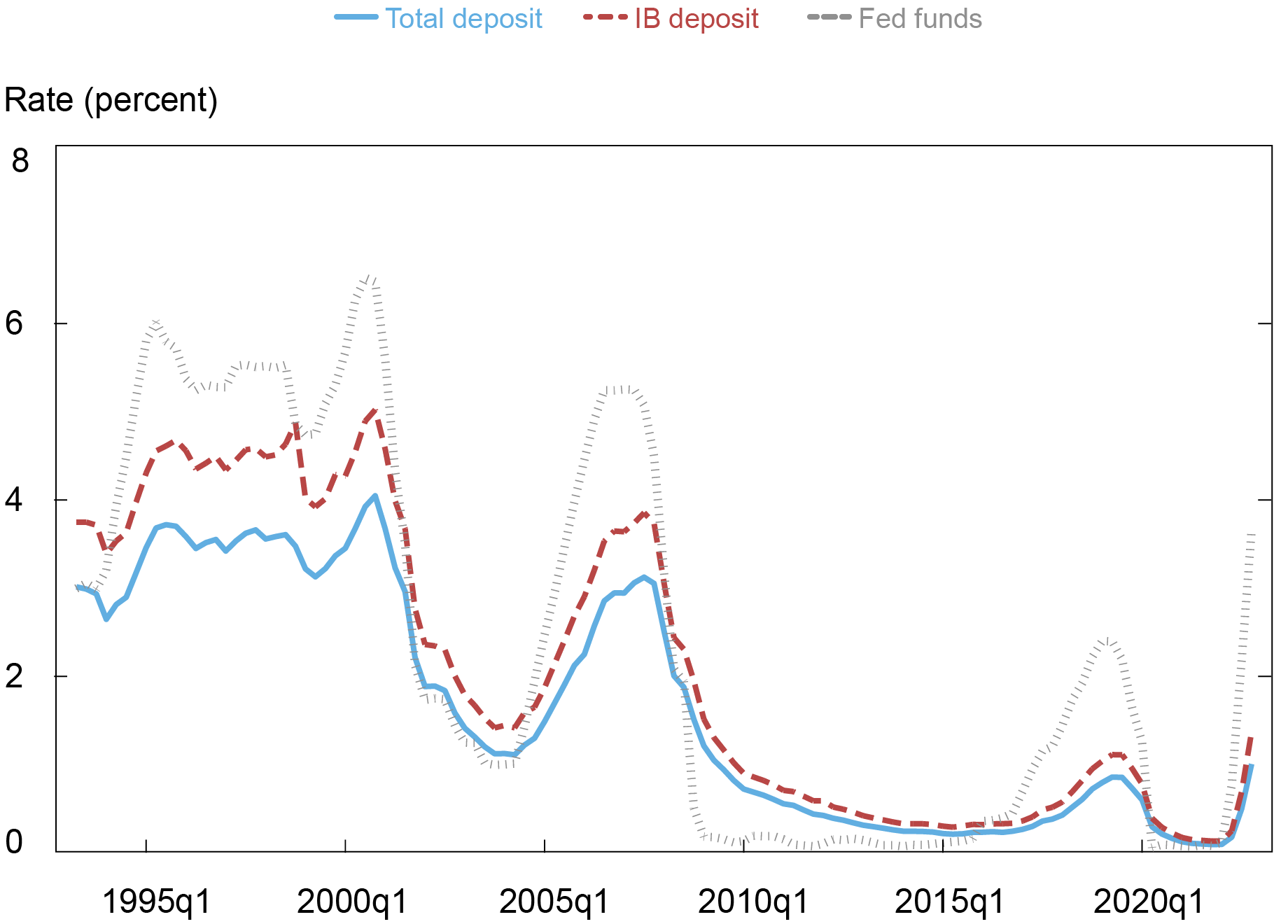

The chart below illustrates the behavior of deposit rates over the past thirty years along with the daily average effective fed funds rate. Deposit rates tend to lag changes in the fed funds rate, particularly during a rising interest rate environment. In 2022:Q4, the average fed funds rate reached 3.7 percent and interest-bearing deposit rates reached 1.4 percent.

Deposit Rates Lag the Fed Funds Rate

Notes: This chart plots the average rate of interest expense on total deposits and interest-bearing (IB) deposits relative to the average corresponding deposit balance for the industry (all bank holding companies).

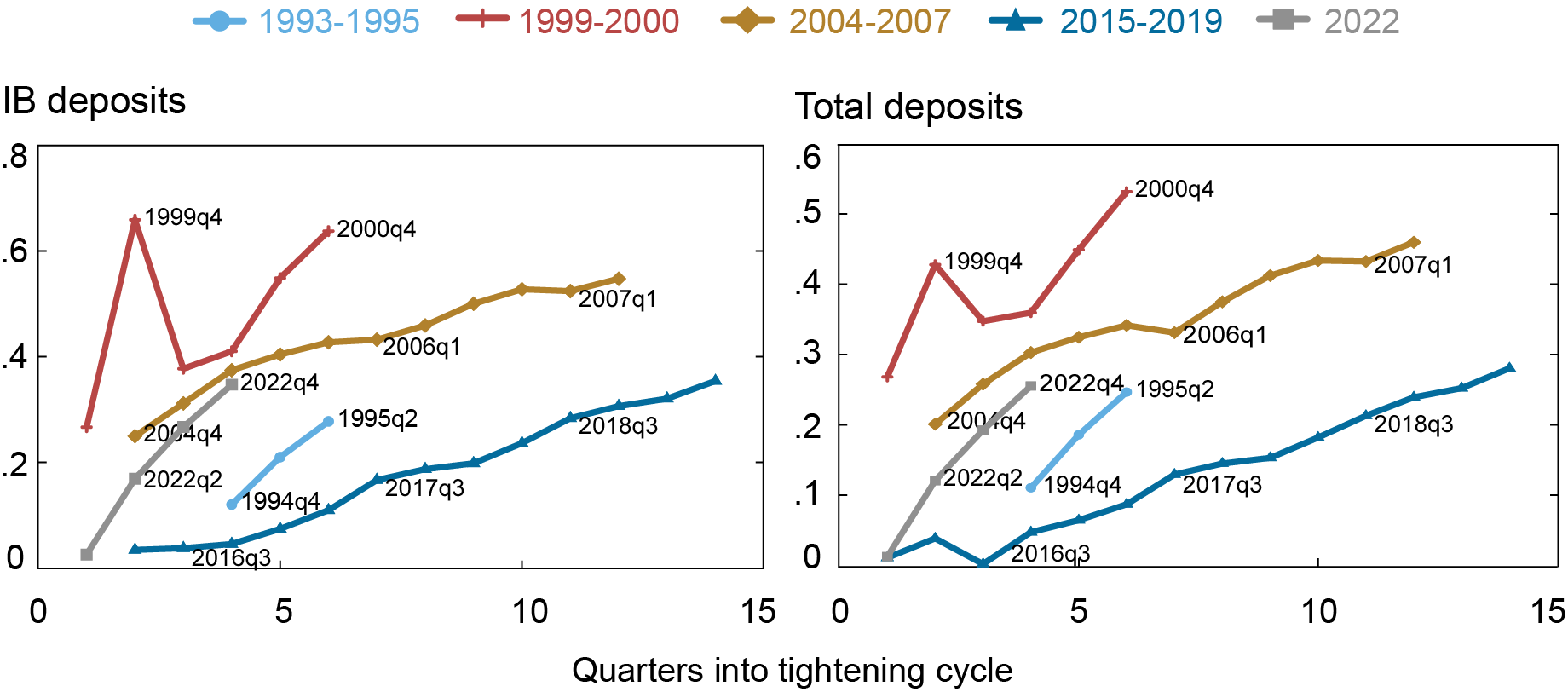

As noted above, deposit betas are a measure of the pass-through of monetary policy to the deposit market. More specifically, the deposit beta is the portion of a change in the fed funds rate that is passed on to the deposit rate. Deposit betas can be calculated for individual changes in the fed funds rate or as a cumulative measure over a tightening cycle. The charts below summarize the cumulative change in deposit rates relative to the cumulative change in the fed funds rate over the last five tightening cycles. During 2022:Q4, the cumulative IB deposit beta increased to almost 0.4. This is on par with the peak beta in the rate-hike cycle of 2015-19, but the beta has risen much faster in the current cycle, reaching to almost 0.4 in one year instead of the three years it took in the prior cycle.

Cumulative Deposit Betas Continue to Rise

Notes: These charts plot the cumulative deposit beta over interest-rate tightening cycles since 1995. Cumulative betas are the change in interest expense on interest-bearing (IB) deposits (left panel) or total deposits (right panel) relative to the change in the average effective fed funds rate. Interest expense is calculated at the industry level (all bank holding companies) by dividing interest expense on deposits by the average IB deposit balance (left panel) or the total deposit balance (right panel) in the quarter.

Deposit Gap

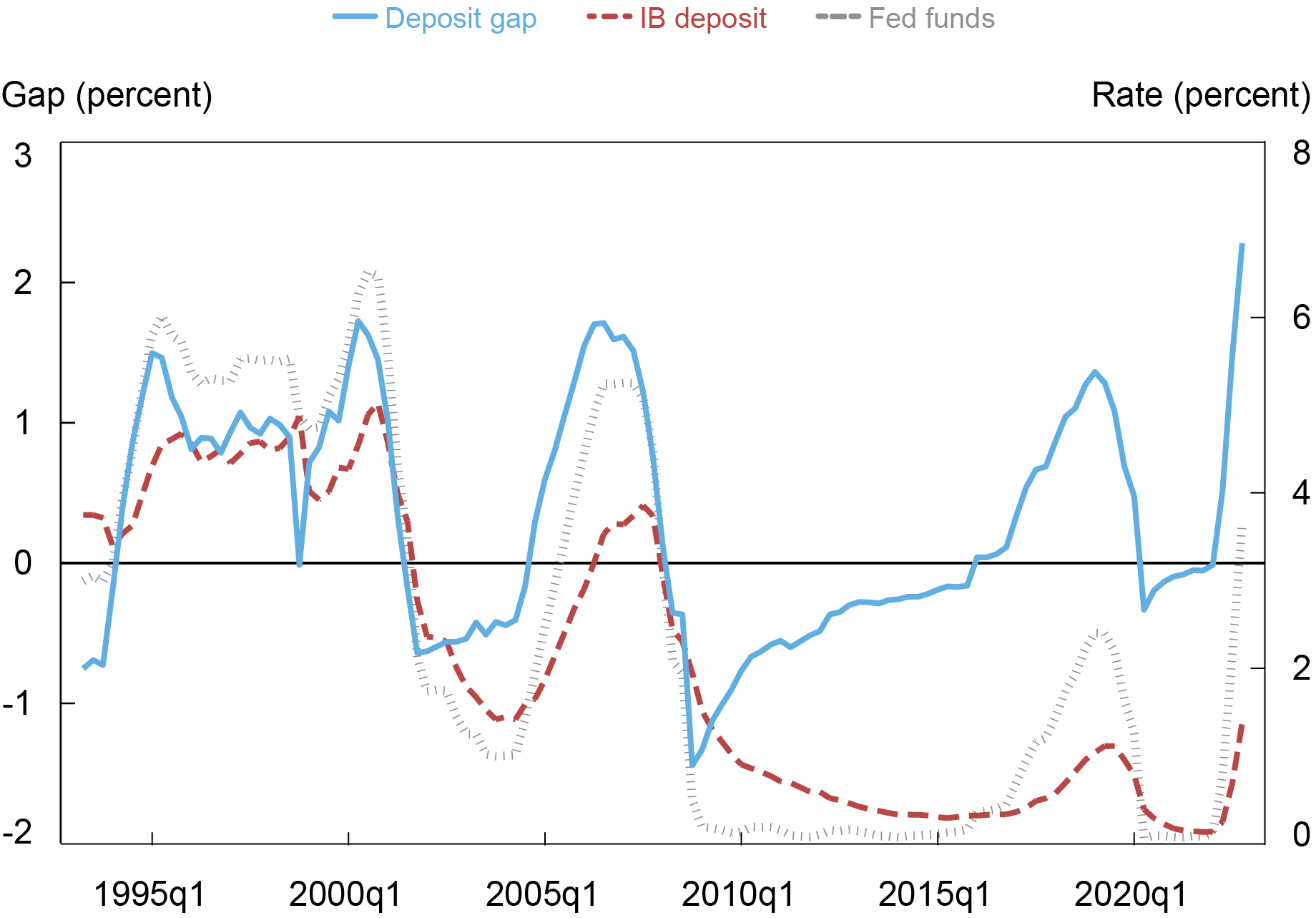

One reason for the markedly higher speed of adjustment is the rapid pace of interest rate increases in the current hiking cycle. As the fed funds rate rises faster than deposit rates, the gap between the fed funds rate and the deposit rate increases. This gap is indicative of the opportunity cost for depositors relative to other investment vehicles (see recent analysis on Liberty Street Economics). The chart below illustrates that the spread between the fed funds rate and the deposit rate is at a modern high of above 2 percent. Hence, banks are facing significant competition for savers from other vehicles that offer rates closer to the fed funds rate, such as money market mutual funds. While deposit rates and deposit betas have continued to rise, they have not outpaced the growth in the fed funds rate—a development suggesting that both deposit rates and betas are likely to continue to rise during 2023.

The Spread between Fed Funds and Deposit Rates Has Widened

Note: IB is interest-bearing.

Funding Ratios

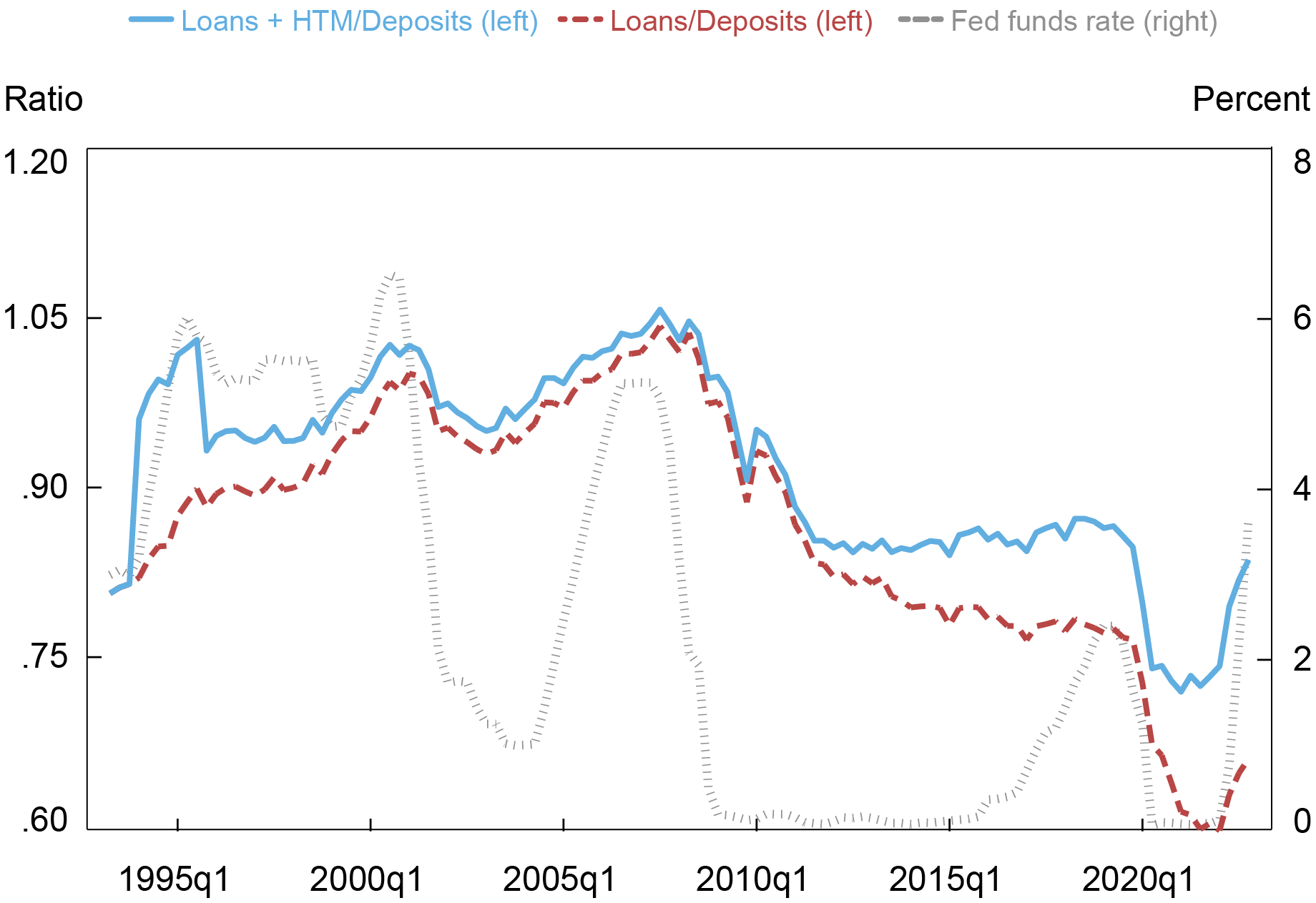

In our previous post on this topic, we examined how deposit betas were related to the ratio of lending (either loans or loans and held-to-maturity securities) to deposits. Lending-to-deposit ratios are measures of how much banks might need deposits. If deposit supply is high, then the lending-to-deposit ratio will be low, and banks are more easily able to fund all their desired loans and have no incentive to attract additional deposits. If deposit supply is low, then the lending-to-deposit ratio will be high, and banks might need to seek additional funding. The implication is that the deposit beta varies over time depending on the funding needs of banks.

Funding Ratios Continue to Tighten

Note: HTM refers to held-to-maturity securities.

Since our last post, indicators of deposit supply relative to bank investment opportunities have tightened but have not yet reached pre-COVID levels. This rise was initially driven by a decrease in deposits; between 2021:Q4, just before the start of the current tightening cycle, and 2022:Q4, total deposits for BHCs have fallen by roughly $220 billion. However, in 2022:Q4, deposit quantities were stable but lending and securities grew, further raising the funding ratios.

The Composition of Funding

The stabilization of funding quantities masks important shifts in the composition of deposit funding on bank balance sheets. Overall deposits are fungible: non-interest-bearing deposits can migrate to interest-bearing accounts, reflecting checking deposits moving to savings accounts or certificates of deposits (CDs). To retain deposits, banks strategically raise rates on specific categories of deposits without re-pricing all deposits.

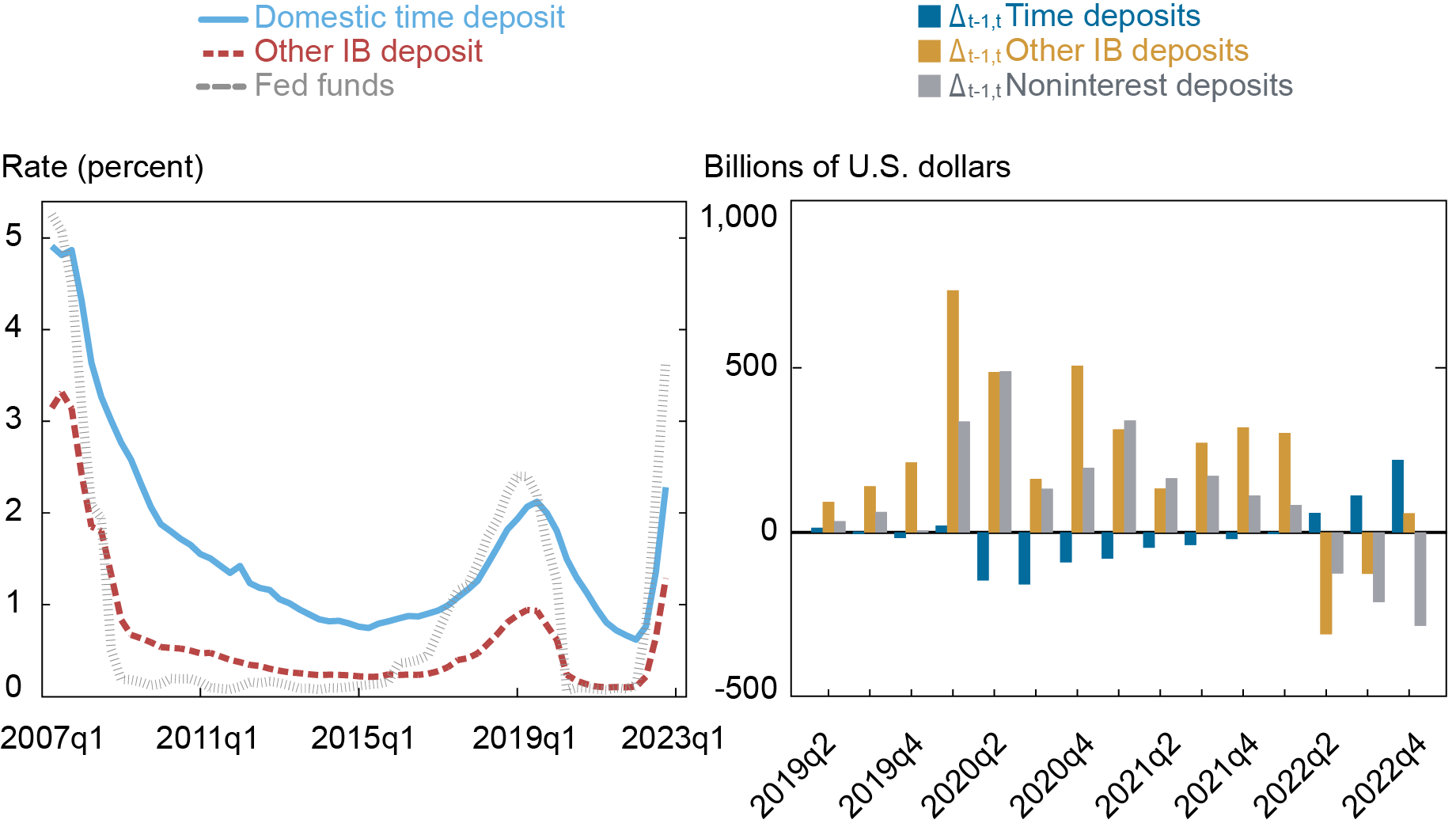

In the left panel of the chart below, we compare deposit rates for domestic time deposits (for example, CDs) to other types of deposits (foreign deposits, savings accounts, and money market accounts) since 2007:Q1. Rates on time deposits are typically higher, but also rise more in response to a higher fed funds rate.

Pricing and Quantities Vary across Deposit Type

Note: IB is interest-bearing.

The right panel of the chart demonstrates the behavior of deposit quantities in the recent period. Beginning in 2022:Q2, non-interest-bearing deposits and other IB deposits began to fall, but this decline was somewhat offset by the rise in time deposits.

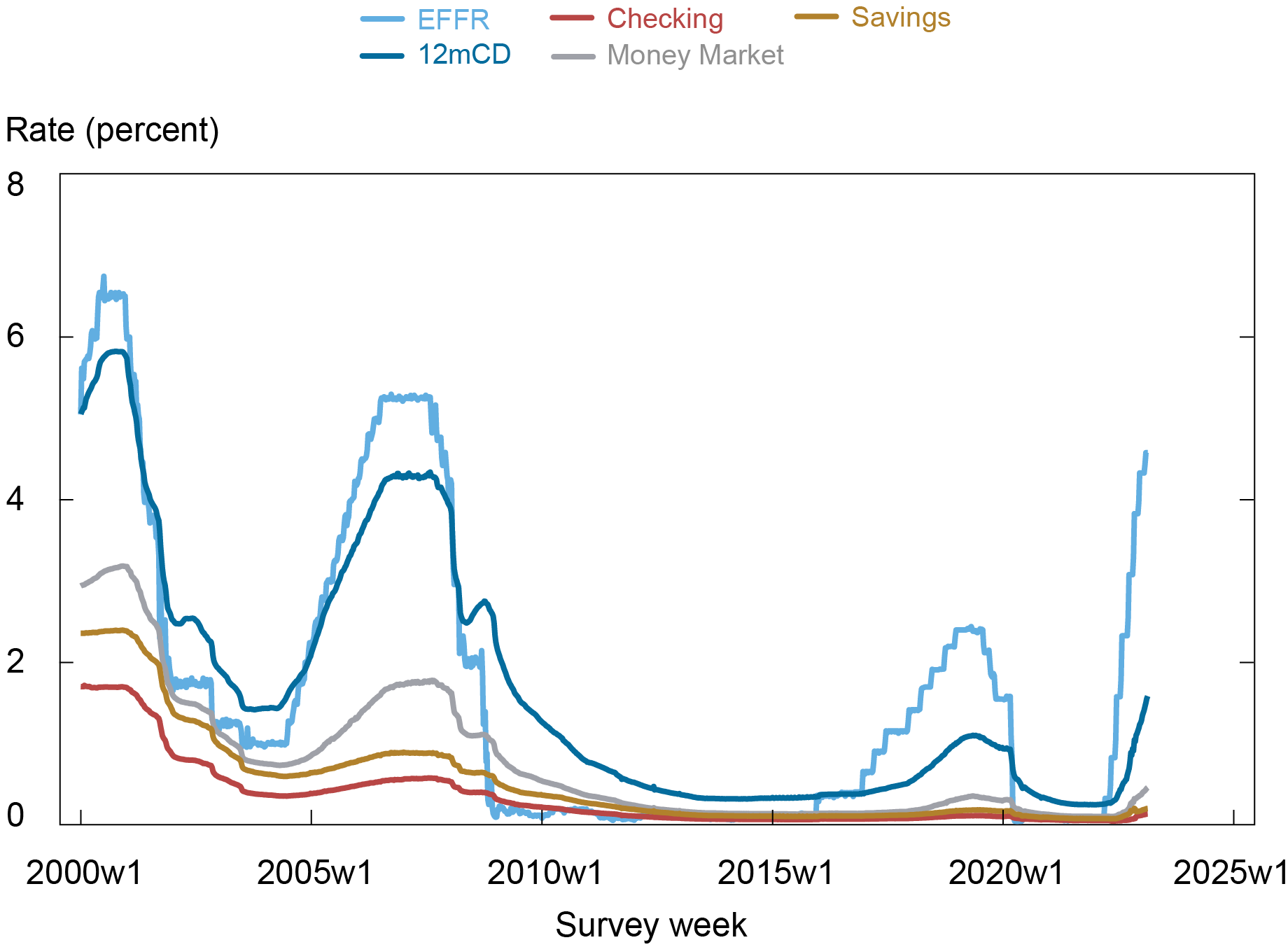

Using RateWatch survey data, we observe how banks strategically differentiate between products for retail depositors. In the next chart, rates offered for twelve-month CDs have risen more than for money market deposit accounts—which are in turn more responsive than savings accounts, which themselves are more responsive than checking accounts. Overall, banks are raising rates on specific categories of deposits and that is being reflected in the composition of deposits.

Offered Deposit Rates Are Rising Faster for CDs

Notes: EFFR is effective federal funds rate. CD is certificate of deposit.

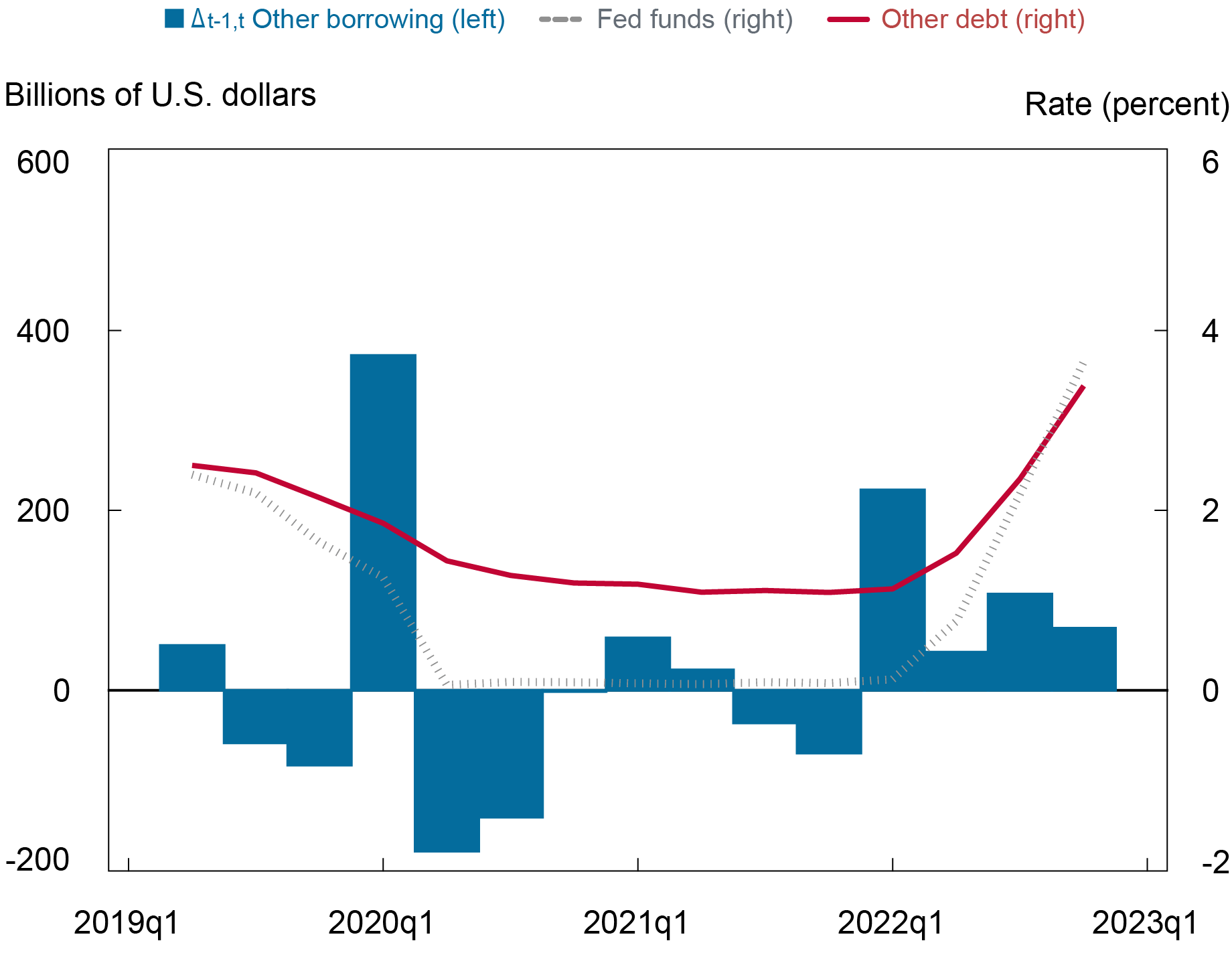

In addition to raising rates on specific types of deposits, banks are increasingly seeking out non-deposit funding. The chart below shows the changes in other borrowing (subordinated debt, trading liabilities, and other borrowing) and the implied rate paid on these debts. Other borrowing grew by $440 billion in 2022, more than offsetting deposit losses, albeit at higher rates than what deposits pay. The rates paid on other forms of borrowing are typically higher than the fed funds rate and, by extension, deposit rates. For instance, in the recent past, the most common form of non-deposit borrowing are FHLB advances. FHLB advances are a type of secured wholesale funding for which banks are typically required to pay a rate above the risk-free rate and thus above deposit rates.

Non-Deposit Borrowing Is Increasing

Takeaways

Deposit rates continue to lag the fed funds rate, but the pass-through of policy rates is quickly approaching levels not seen since the early 2000s. The rapid rise in rates has resulted in a fall in overall deposit balances, a tightening of funding ratios, and an increase in non-deposit borrowing. Banks have been managing the deposit runoff using more attractive time-deposit rates and other borrowings. Given the increase in fed funds rates since 2022:Q4 and the wide gap between deposit rates and the fed funds rate, we expect that deposits will continue to shift into higher rate categories that are more responsive to monetary policy.

Alena Kang-Landsberg is a research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Stephan Luck is a financial research advisor in Banking Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Matthew Plosser is a financial research advisor in Banking Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Alena Kang-Landsberg, Stephan Luck, and Matthew Plosser, “Deposit Betas: Up, Up, and Away?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, April 11, 2023, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2023/04/deposit-betas-up-up-and-away/

BibTeX: View |

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics