In our previous post, we documented the significant growth of nonbank financial institutions (NBFIs) over the past decade, but also argued for and showed evidence of NBFIs’ dependence on banks for funding and liquidity support. In this post, we explain that the observed growth of NBFIs reflects banks optimally changing their business models in response to factors such as regulation, rather than banks stepping away from lending and risky activities and being substituted by NBFIs. The enduring bank-NBFI nexus is best understood as an ever-evolving transformation of risks that were hitherto with banks but are now being repackaged between banks and NBFIs.

Banks and NBFIs Are Interwoven

The common view is that banks and NBFIs operate in parallel, performing different activities, or they act as substitutes of each other, performing substantially similar activities, with banks inside and NBFIs outside the perimeter of prudential regulation. We argue instead that NBFI and bank activities and risks are so interwoven that they are better described as having transformed over time rather than as being unrelated or having simply migrated from banks to NBFIs.

What activities and risks of the banking sector have been subject to this transformation process? In our recent paper, we propose a taxonomy of such risk transformations and document with a variety of examples and data analysis the specific connections between banks and NBFIs that make each transformation possible. We identify three main categories of intermediation activities that historically have been provided mainly by banks and that are now increasingly in the NBFI domain. The table below summarizes our perspective.

Corporate and Mortgage Loans

Traditionally, banks held corporate and mortgage loans on their balance sheets, but due at least in part to higher capital requirements and tighter regulations, these loans are increasingly held by NBFIs. However, banks have retained indirect loan exposures to NBFI lenders, such as via senior loans to private credit companies or collateralized loans to mortgage real estate investment trusts. Thus, the banks’ risks have transformed from exposure to the loans into exposures to NBFI balance sheets.

Transformations of Intermediation Activities Across the NBFI and Bank Sectors

| Transformation | Activities and Products Historically Within the Banking System | Activities and Products Spread Across Banks and NBFIs |

|---|---|---|

| Loans and Mortgages Loans shift from being made and held by banks to being made by NBFIs with collateralized or senior financing provided by banks. | Corporate loans Mortgage loans | Banks make senior loans to private credit companies. Banks make collateralized loans to mortgage real estate investment trusts (REITs). Banks hold senior tranches of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and collateralized loan obligations (CLOs). |

| Activities Using Short-Term Funding Activities that require short-term funding transform from being conducted and funded by banks to being conducted by nonbanks and funded by banks. | Mortgage, CLO, and other asset-backed security (ABS) origination Acquisition/leveraged buyout (LBO) financing Mortgage servicing | Banks offer warehouse financing to nonbank mortgage, CLO, and other ABS originators. Banks make short-term loans to private equity companies, including subscription finance loans. Banks sponsor commercial paper (CP) or directly lend to nonbank mortgage servicers. |

| Contingent Funding While the footprint of NBFIs has grown relative to that of banks, banks retain responsibility for providing contingent funding in the form of credit lines to the NBFI sector. | Credit lines to nonfinancial businesses OTC bilateral derivatives | Banks provide credit lines to NBFIs to be drawn down during periods of stress. Banks bear mutualized counterparty risk as derivative clearinghouse members and provide credit lines to NBFIs to meet margin requirements. |

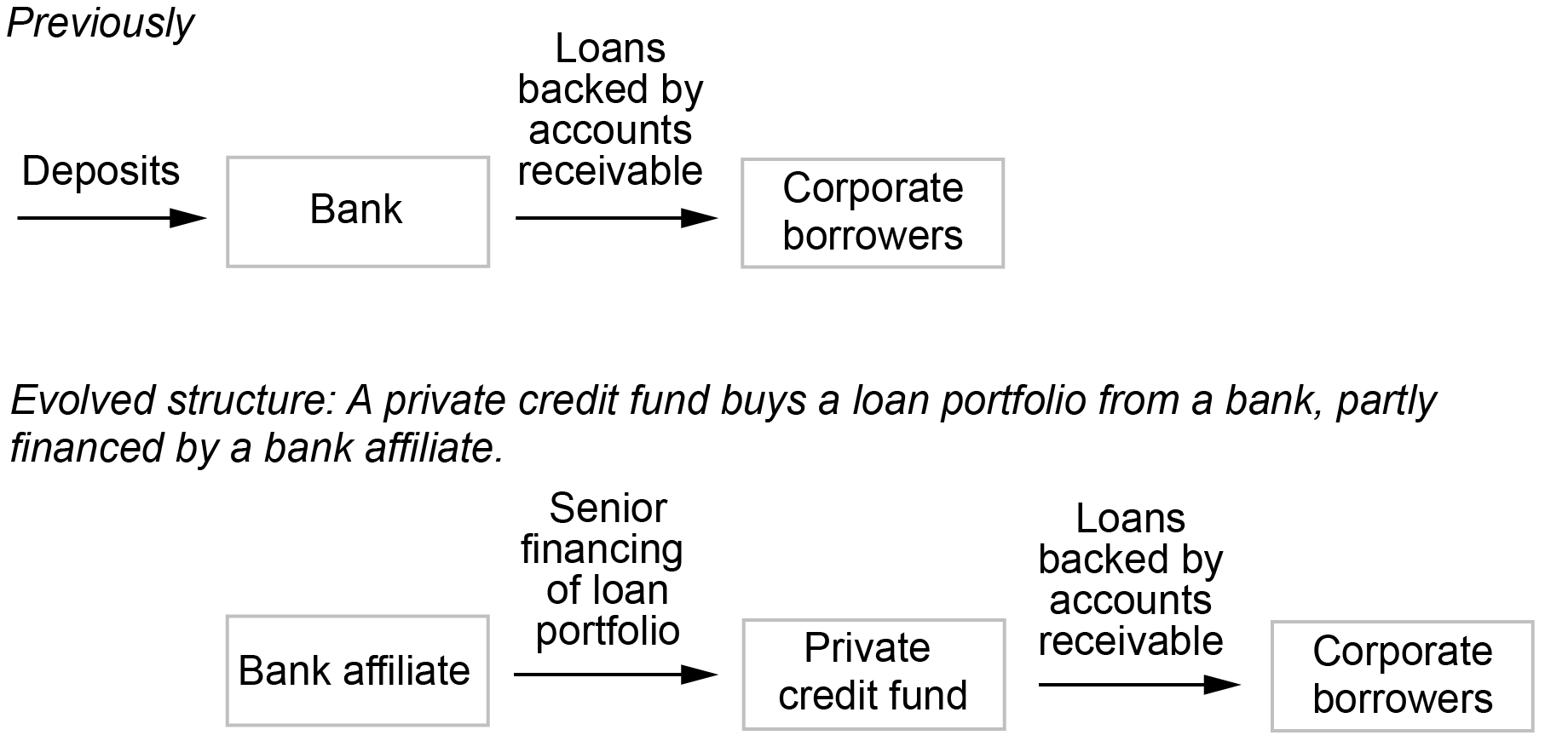

A specific example of this transformation comes from the booming private credit market. NBFIs’ footprint in this segment is growing fast but not without the support of banks. For instance, in June 2023, PacWest bank sold its specialty finance loan portfolio to Ares Management, one of the largest private fund managers in the world. The purchase of these loans, however, was financed in part by a subsidiary of Barclays, another banking organization. Hence, while the loans left the banking system, some of the bank exposures returned through the financing of Ares’ purchase by Barclays. The figure below illustrates a representative transaction of this type and the associated transformation of risks and activities.

An Example of Transformation in the Corporate Credit Market—Bank Loans on Accounts Receivable

Credit Activity Using Short-Term Funding

Short-term funding is needed for various credit products such as securitization, financing acquisitions, and mortgage servicing. These activities used to be provided by banks but are now dominated by NBFIs, who nevertheless receive funding from banks through direct loans, warehouse financing, credit lines, and commercial paper.

Consider mortgage servicing. Banks’ share of servicing rights has fallen to about 30 percent. While this shift towards NBFIs appears to move risk away from banks, the latter are providing warehouse credit lines to nonbank mortgage originators, who draw down these lines as they make or purchase mortgage loans and then pay off these drawdowns as they sell the loans into securitizations. Further, banks finance the payment advances required of nonbank mortgage servicers either through credit lines or by sponsoring the issuance of commercial paper. Hence, the funding risks of mortgage origination and servicing remain with banks through their exposures to NBFI servicing activities.

Contingent Funding

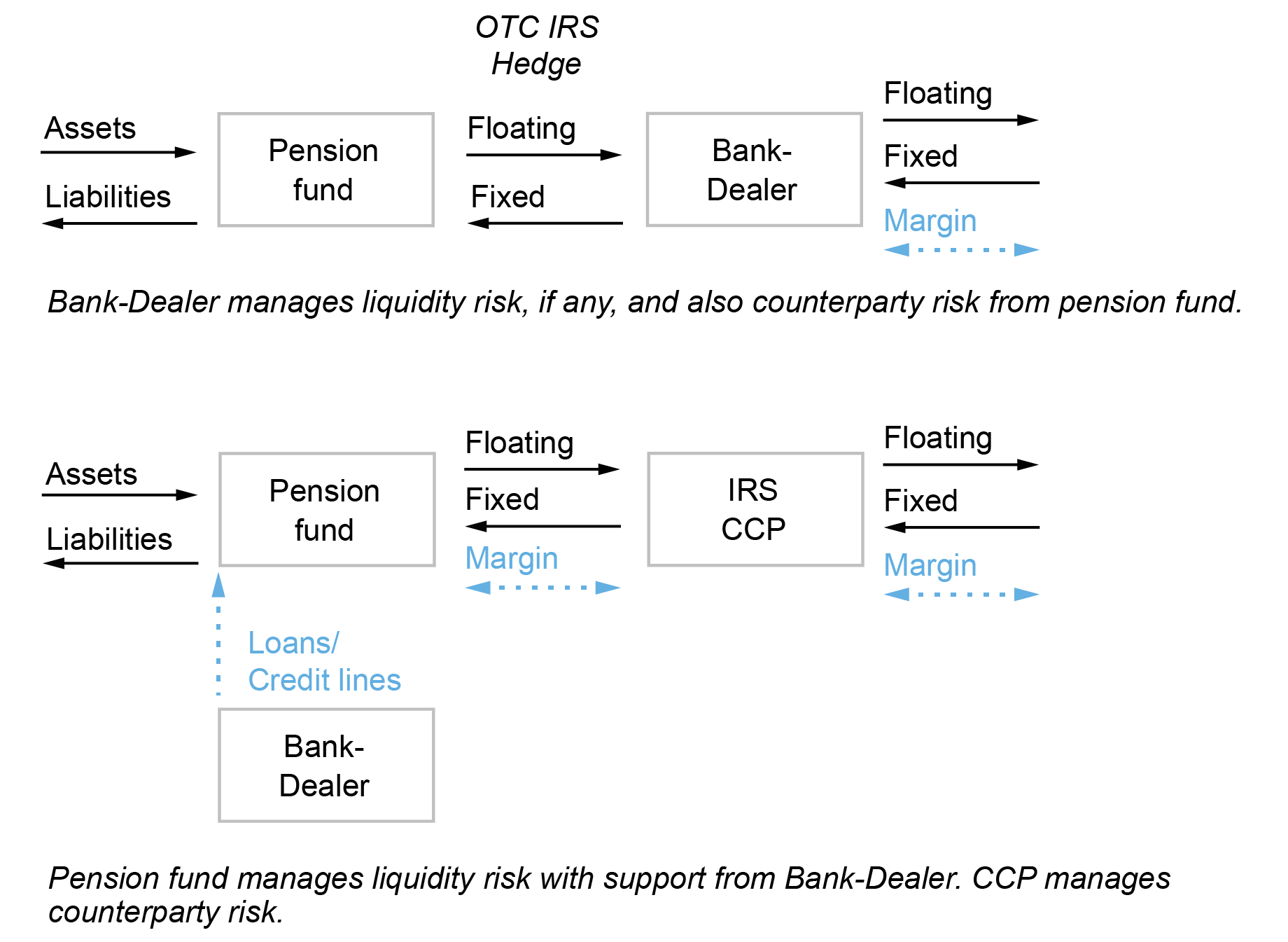

As we posited in our previous blog, intermediation activity requires access to liquidity insurance associated with the provision of unusual or emergency short-term funding. An interesting example is the evolving role of banks in derivatives clearing. Following the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2007-08, regulators mandated that most derivatives (previously cleared bilaterally and traded over the counter) should be centrally cleared. While NBFIs previously engaged with banks in bilateral transactions, under the new mandate, they engage with clearing houses instead. To meet clearing houses’ calls for initial and variation margins, NBFIs need contingent liquidity that is provided by banks in the forms of credit lines. Hence, the central clearing mandate has transformed the counterparty risk that banks previously faced to liquidity risk.

The figure below illustrates this transformation using the example of the U.K. pension funds. The top schematic shows a bank-dealer with a pre-GFC, bilateral interest-rate swap (IRS) facing a pension fund. With this arrangement, the bank-dealer bears counterparty risk from the trade and may have to manage its own liquidity risk from margin calls on the IRS that it executes with other dealers to hedge its exposure to the pension fund. The bottom schematic shows a pension fund with a post-GFC IRS cleared against a central counterparty (CCP), which requires the pension fund to post initial margin and to be prepared to make variation margin calls. This fund’s direct counterparty is the CCP. However, in order to manage its margin requirements, the fund engages a bank to make loans to cover the initial margin, and to provide credit lines to finance variation margin payments and increases in initial margin requirements. During the well-known UK gilt-market distress experienced in September 2022, both the extent of this reliance on banks and the implications for the propagation of distress became apparent.

Liquidity Risk from Derivatives Clearing: U.K. Pensions

NBFIs and Banks: You Can’t Have One Without the Other

This post and the previous one have proposed a view of financial intermediation where banks and NBFIs are complementary to one another, rather than acting in parallel or as substitutes. Activities and related risks of banks and nonbanks remain intimately connected, indeed in a symbiotic relationship, even as banks withdraw from direct participation in certain activities owing to increased costs and restrictions stemming from capital and liquidity requirements, living wills requirements, and other measures.

We believe this transformation view, where risks do not migrate away from the banking system but are instead optimally repackaged between banks and NBFIs, provides innovative insights into observed trends in the financial intermediation industry. Equally important, it offers conceptual clarity that allows regulators to monitor activities and assess risk holistically in the financial sector, encompassing both banks and NBFIs. For instance, one implication of this transformation view is that both sides will be exposed to one another in crises, suggesting possibly bi-directional channels of shock transmission and amplification. We consider this aspect of the bank-NBFI risk propagation, and the related policy implications, in the next post.

Viral V. Acharya is a professor of finance at New York University Stern School of Business.

Nicola Cetorelli is the head of Non-Bank Financial Institution Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Bruce Tuckman is a professor of finance at New York University Stern School of Business.

How to cite this post:

Viral V. Acharya, Nicola Cetorelli, and Bruce Tuckman, “Banks and Nonbanks Are Not Separate, but Interwoven,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, June 18, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/06/banks-and-nonbanks-are-not-separate-but-interwoven/.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics