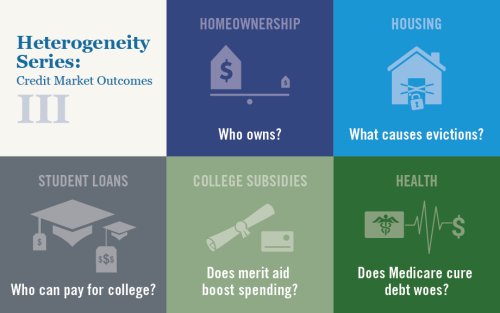

Average economic outcomes serve as important indicators of the overall state of the economy. However, they mask a lot of underlying variability in how people experience the economy across geography, or by race, income, age, or other attributes. Following our series on heterogeneity broadly in October 2019 and in labor market outcomes in March 2020, we now turn our focus to further documenting heterogeneity in the credit market. While we have written about credit market heterogeneity before, this series integrates insights on disparities in outcomes in various parts of the credit market. The analysis includes a look at differing homeownership rates across populations, varying exposure to foreclosures and evictions, and uneven student loan burdens and repayment behaviors. It also covers heterogeneous effects of policies by comparing financial health outcomes for those with access to public tuition subsidies and Medicare versus those not eligible. The findings underscore that a measure of the average, particularly relating to policy impact, is far from complete. Rather, a sharper picture of the diverse effects is essential to understanding the efficacy of policy.

Here is a brief look at each post in the series:

1. Inequality in U.S. Homeownership Rates by Race and Ethnicity

1. Inequality in U.S. Homeownership Rates by Race and Ethnicity

Andrew Haughwout, Donghoon Lee, Joelle Scally, and Wilbert van der Klaauw investigate racial gaps in homeownership rates and, importantly, explore the reasons behind these differences. They find:

- The Black-white and Black-Hispanic homeownership gaps widened after the Great Recession, markedly more so after 2015.

- The foreclosure crisis disproportionately affected areas with majority Black or Hispanic populations.

- Explanations for the homeownership gap may include differential effects of tightening underwriting standards across areas with a majority Black or Hispanic population versus those with a majority white population, differences in labor market outcomes across these areas during and following the Great Recession, and larger incidence of student debt in these areas.

2. Who Has Been Evicted and Why?

2. Who Has Been Evicted and Why?

Andrew Haughwout, Haoyang Liu, and Xiaohan Zhang explore the reasons behind evictions, who is more likely to be evicted, and the possibility of owning a home and gaining access to credit following evictions. Their findings reveal:

- Large shares of low-income households have been evicted.

- Income or job loss and change in building ownership are important reasons behind evictions.

- Renters with a past eviction history are less likely to have access to credit cards and auto loans.

3. Measuring Racial Disparities in Higher Education and Student Debt Outcomes

3. Measuring Racial Disparities in Higher Education and Student Debt Outcomes

Rajashri Chakrabarti, William Nober, and Wilbert van der Klaauw investigate whether (and how) differences in college attendance rates and types of college attended may lead to student debt borrowing and default. The key takeaways include:

- There are noticeable disparities in college attendance and graduation rates between majority white, majority Black, and majority Hispanic neighborhoods, with graduation rates the lowest in majority Black neighborhoods.

- Students from majority Black neighborhoods are more likely to hold student debt and in larger amounts.

- Borrowers from majority Black neighborhoods are more likely to default, and this pattern is more prominent for borrowers from two-year colleges than those from four-year colleges.

4. Do College Tuition Subsidies Boost Spending and Reduce Debt? Impacts by Income and Race

4. Do College Tuition Subsidies Boost Spending and Reduce Debt? Impacts by Income and Race

Rajashri Chakrabarti, William Nober, and Wilbert van der Klaauw investigate the effect of tuition subsidies, specifically merit-based aid, on other debt and consumption outcomes. The main findings include:

- Cohorts eligible for these tuition subsidies have higher credit card balances and higher delinquencies in their early-to-mid-twenties. These patterns are more evident for borrowers from low-income and predominantly Black neighborhoods.

- Eligible cohorts are more likely to own cars (as captured by auto debt originations) in their early-to-mid-twenties. This pattern is more prominent for borrowers from low-income and predominantly Black neighborhoods.

- The patterns indicate substitution away from student debt (as net tuition declines) to other forms of consumer debt for eligible cohorts in college-going ages, a pattern more prominent for borrowers from low-income and Black neighborhoods.

5. Medicare and Financial Health across the United States

5. Medicare and Financial Health across the United States

Paul Goldsmith-Pinkham, Maxim Pinkovskiy, and Jacob Wallace investigate the effect of access to health insurance programs, as captured by Medicare eligibility, on financial health of individuals. They find:

- Medicare eligibility markedly improves financial health, as captured by declines in debt in collections.

- Access to Medicare drastically reduces geographic disparities in financial health.

- The improvements in financial health are most evident in areas with a high share of Black, low-income, and disabled residents and in areas with for-profit hospitals.

As these posts will demonstrate in greater detail tomorrow, the average outcome doesn’t provide a full picture of credit market outcomes. There is considerable heterogeneity in different segments of the credit market both in terms of outcomes, as well as the in the effects of specific policies. Outcomes vary by a range of factors, such as differences in race, income, age, and geography. We will continue to study and write about the importance of heterogeneity in the credit market and other segments of the economy.

Rajashri Chakrabarti is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Rajashri Chakrabarti is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Rajashri Chakrabarti, “Introduction to Heterogeneity Series III: Credit Market Outcomes,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, July 7, 2020, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/06/introduction-to-heterogeneity-series-iii-credit-market-outcomes.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics