Why Do Banks Fail? Bank Runs Versus Solvency

Evidence from a 160-year-long panel of U.S. banks suggests that the ultimate cause of bank failures and banking crises is almost always a deterioration of bank fundamentals that leads to insolvency. As described in our previous post, bank failures—including those that involve bank runs—are typically preceded by a slow deterioration of bank fundamentals and are hence remarkably predictable. In this final post of our three-part series, we relate the findings discussed previously to theories of bank failures, and we discuss the policy implications of our findings.

Why Do Banks Fail? The Predictability of Bank Failures

Can bank failures be predicted before they happen? In a previous post, we established three facts about failing banks that indicated that failing banks experience deteriorating fundamentals many years ahead of their failure and across a broad range of institutional settings. In this post, we document that bank failures are remarkably predictable based on simple accounting metrics from publicly available financial statements that measure a bank’s insolvency risk and funding vulnerabilities.

Why Do Banks Fail? Three Facts About Failing Banks

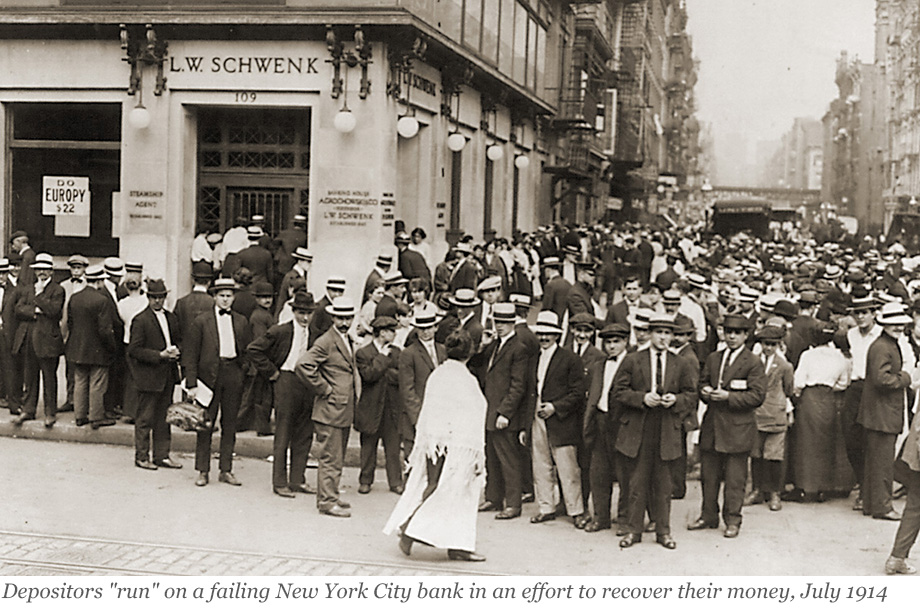

Why do banks fail? In a new working paper, we study more than 5,000 bank failures in the U.S. from 1865 to the present to understand whether failures are primarily caused by bank runs or by deteriorating solvency. In this first of three posts, we document that failing banks are characterized by rising asset losses, deteriorating solvency, and an increasing reliance on expensive noncore funding. Further, we find that problems in failing banks are often the consequence of rapid asset growth in the preceding decade.

Deposits and the March 2023 Banking Crisis—A Retrospective

In this post, we evaluate how deposits have evolved over the latter portion of the current monetary policy tightening cycle. We find that while deposit betas have continued to rise, they did not accelerate following the bank runs in March 2023. In addition, while overall deposit funding has remained stable, we find that the banks most affected by the March 2023 events are offering higher deposit rates and are growing their deposit funding relative to the broader banking industry.

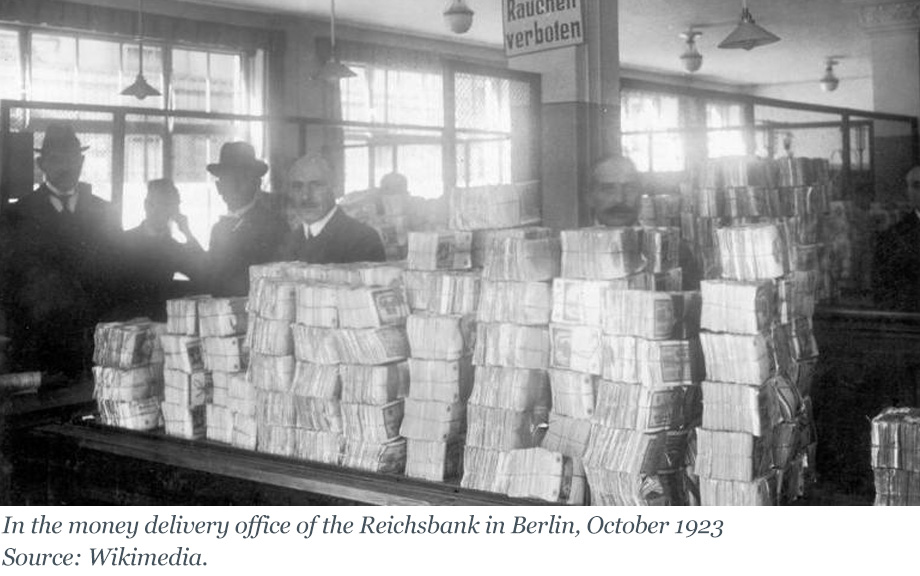

Inflating Away the Debt: The Debt‑Inflation Channel of German Hyperinflation

The recent rise in price pressures around the world has reignited interest in understanding how inflation transmits to the real economy. Economists have long recognized that unexpected surges of inflation can redistribute wealth from creditors to debtors when debt contracts are written in nominal terms (see, for example, Fisher 1933). If debtors are financially constrained, this redistribution can affect real economic activity by relaxing financing constraints. This mechanism, which we call the debt-inflation channel, is well understood theoretically (for example, Gomes, Jermann, and Schmid 2016), but there is limited empirical evidence to substantiate it. In this post, we discuss new insights from one of the key events in monetary history: the Great German Inflation of 1919-23. Because this case of inflation was both surprising and extremely high, Germany’s experience helps shed light on how high inflation impacts firms’ economic activity through the erosion of their nominal debt burdens. These insights are based on a recently released research paper.

Bank Funding during the Current Monetary Policy Tightening Cycle

Recent events have highlighted the importance of understanding the distribution and composition of funding across banks. Market participants have been paying particular attention to the overall decline of deposit funding in the U.S. banking system as well as the reallocation of deposits within the banking sector. In this post, we describe changes in bank funding structure since the onset of monetary policy tightening, with a particular focus on developments through March 2023.

Deposit Betas: Up, Up, and Away?

Deposits make up an $18 trillion market that is simultaneously the main source of bank funding and a critical tool for households’ financial management. In a prior post, we explored how deposit pricing was changing slowly in response to higher interest rates as of 2022:Q2, as measured by a “deposit beta” capturing the pass-through of the federal funds rate to deposit rates. In this post, we extend our analysis through 2022:Q4 and observe a continued rise in deposit betas to levels not seen since prior to the global financial crisis. In addition, we explore variation across deposit categories to better understand banks’ funding strategies as well as depositors’ investment opportunities. We show that while regular deposit funding declines, banks substitute towards more rate-sensitive forms of finance such as time deposits and other forms of borrowing such as funding from Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLBs).

How Do Interest Rates (and Depositors) Impact Measures of Bank Value?

The rapid rise in interest rates across the yield curve has increased the broader public’s interest in the exposure embedded in bank balance sheets and in depositor behavior more generally. In this post, we consider a simple illustration of the potential impact of higher interest rates on measures of bank franchise value.

Insights from Newly Digitized Banking Data, 1867‑1904

Call reports—regulatory filings in which commercial banks report their assets, liabilities, income, and other information—are one of the most-used data sources in banking and finance. Though call reports were collected as far back as 1867, the underlying data are only easily accessible for the recent past: the mid-1980s onward in the case of the FDIC’s FFIEC call reports. To help researchers look farther back in time, we’ve begun creating a complete digital record of this “missing” call report data; this data release covers 1867 through 1904, the bulk of the National Banking Era. Here, we describe the digitization process and highlight some of the interesting features of that era from a research perspective.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics